America Needs a Leader, Not a Salesman

Readers respond to our November 2024 cover story and more.

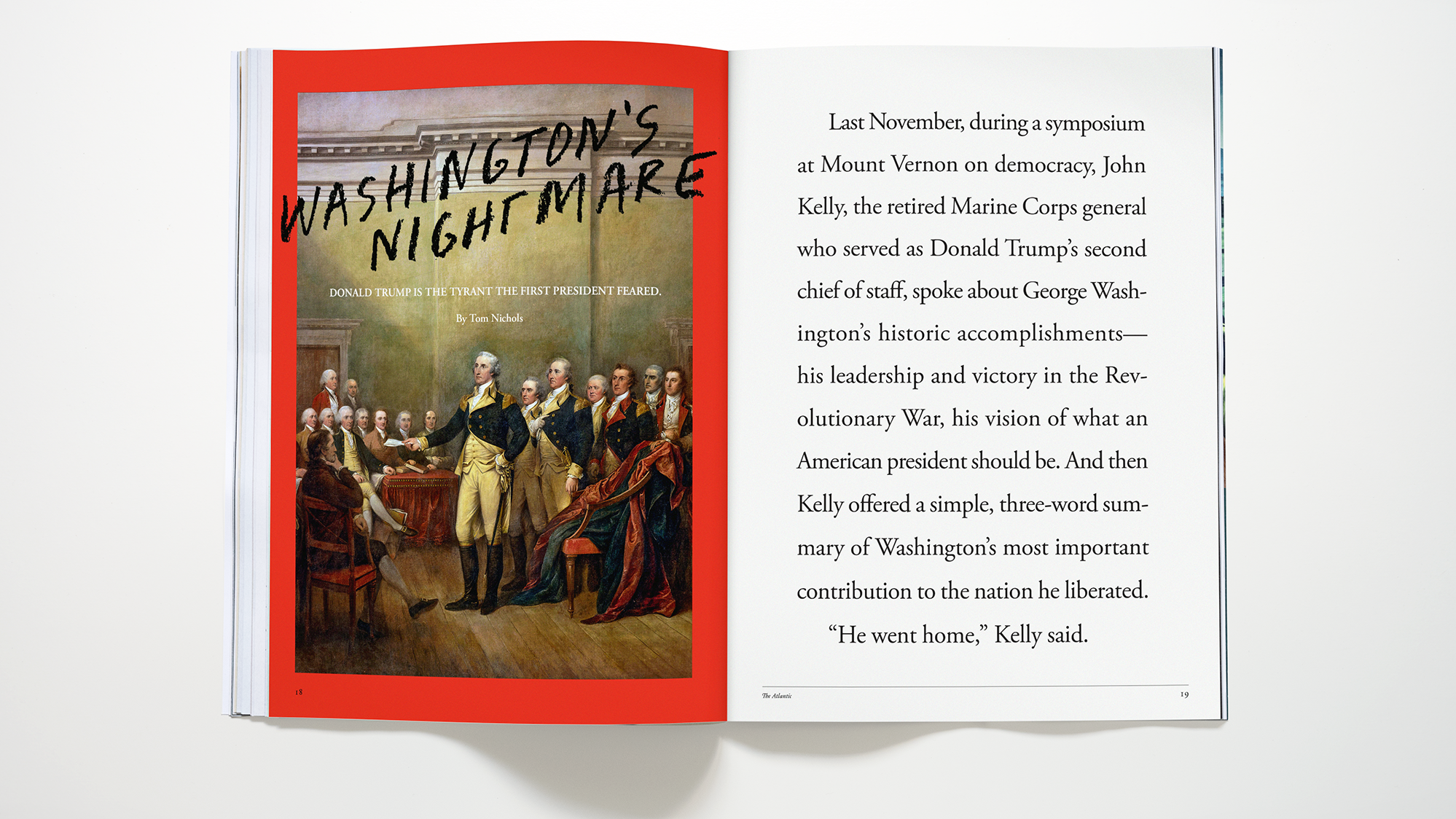

Washington’s Nightmare

Donald Trump is the tyrant the first president feared, Tom Nichols wrote in the November 2024 issue.

Thank you, Tom Nichols, for your timely article profiling our Founding Father. President George Washington modeled key tenets of public service: Be a citizen, serve with integrity, graciously pass the responsibility on to the next citizen. Choosing to juxtapose Washington’s virtues against the abomination that is Donald Trump not only is appropriate, but should serve as a wake-up call to all Americans.

Sadly, it seems many Americans have lost touch with our history. I hope this changes before we find ourselves in a mad scramble to reclaim our more perfect union. Our patriots fought hard for our independence; our forefathers died to keep it. For nearly 250 years, we’ve dedicated ourselves to getting it right.

Do we have any idea what we stand to lose?

Peter Brown

Lyman, Maine

I admire Tom Nichols’s writing and analysis. I teach courses on leadership and ethics at Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service. I conducted a review of 44 peer-reviewed academic-research articles that analyzed various aspects of Trump’s leadership style. My conclusion was that Trump has extremely limited leadership skills. He is a domineering bully who retaliates against anyone who challenges him. His moral decision making is based on self-interest; he lacks emotional intelligence, and his personality is defined by paranoia and victimhood. His principal skill for influencing others is creating an attractive image and selling a product. In times like these, we need a true leader, not a salesman.

Kenneth Williams

Chapel Hill, N.C.

As I read “Washington’s Nightmare,” I returned to the historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge. Dunbar’s book tells the story of a woman enslaved by George and Martha Washington, who fled the president’s residence in 1796. Washington pursued Judge until his death.

The article and book make for a problematic juxtaposition: I, too, celebrate Washington’s achievements, his heroism and devotion to the republic. But Tom Nichols’s sometimes hagiographic treatment of the first president gave me pause. Nichols devotes only one passage—about 150 words—to the problem of Washington and slavery. I understand that his larger interest is in how Washington “set the standard of patriotic character for his successors” and not necessarily in the glaring contradiction of Washington and the people he enslaved. But if one is to compare Washington’s virtues with Trump’s, this contradiction demands attention. Shouldn’t we consider Ona Judge’s nightmare, as she was pursued relentlessly by the Washingtons for having dared to claim what Washington himself had fought for—freedom, dignity, certain unalienable rights? Nichols prominently features General John Kelly’s remark that after serving as president, Washington went home. When the Washingtons returned to Mount Vernon, what did their slaves think?

I’m grateful for Nichols’s assessment of Washington’s legacy. But this aspect of it deserves deeper engagement.

Kevin L. Cole

Sioux Falls, S.D.

Tom Nichols replies:

Thank you to the many readers who appreciated my look back at our first president. I, too, found the distance between George Washington and Donald Trump almost too painful to grasp. Peter Brown raises the real problem of poor historical literacy among Americans, but I wonder if the larger issue is that our politics have become amoral and transactional, something that Washington would have abhorred and that education alone cannot solve. Perhaps Kenneth Williams is closer to the mark by noting that Trump, above all else, is the product of a modern phenomenon—marketing.

I understand Kevin Cole’s objection regarding Washington and slavery, but not every thought and reflection dealing with the first president ought to center on slavery. Washington rebelled against an important institution of his day—monarchism—and to judge him from the 21st century because he did not right one of the other grievous wrongs of the 18th strikes me as ahistorical and, potentially, a diversion from the example he offers us in our current struggle with authoritarianism.

The End of Judicial Independence

One of America’s greatest achievements could disappear overnight, Anne Applebaum wrote in the October 2024 issue.

Anne Applebaum provided an important reminder that some Supreme Court justices appear loyal to President Donald Trump and not the Constitution. But their bad behavior does not end there: Some are loyal, too, to the billionaire class.

Justice Samuel Alito went on an expensive fishing trip with the billionaire Paul Singer, staying at a lodge that charges more than $1,000 a night for a room. Afterward, Alito did not recuse himself from cases involving his benefactor’s hedge fund. Justice Clarence Thomas, not to be outdone, has enjoyed gifts and favors from several billionaires, taking at least 26 flights on private jets. Thomas and Alito claimed that they didn’t know that they were obligated to report these far-from-trivial gifts.

Something has to be done to put an end to this. We need an enforceable code of conduct for the nation’s highest court.

Seth Wittner

Worcester, Mass.

I graduated from law school in 2010. I didn’t know then that those were the halcyon days, when precedents such as Roe v. Wade and its landmark arguments seemed unassailable. I was only 25. I had bought into the teachings about the sanctity of the judiciary’s role in our legal system. I believed—I still believe—in the ethics of my profession, in the dignity of our highest courts and what they and their decisions symbolize. Respect for tradition and the analysis of capable scholars and judges of years past was crucial to my training. But I wonder what younger people sitting in constitutional-law classes must think today, having now witnessed the ugly, frayed edges of our democracy. What do these sobering, disappointing lessons mean for the practice of law in the future?

Brittlynn Mourgue

New York, N.Y.

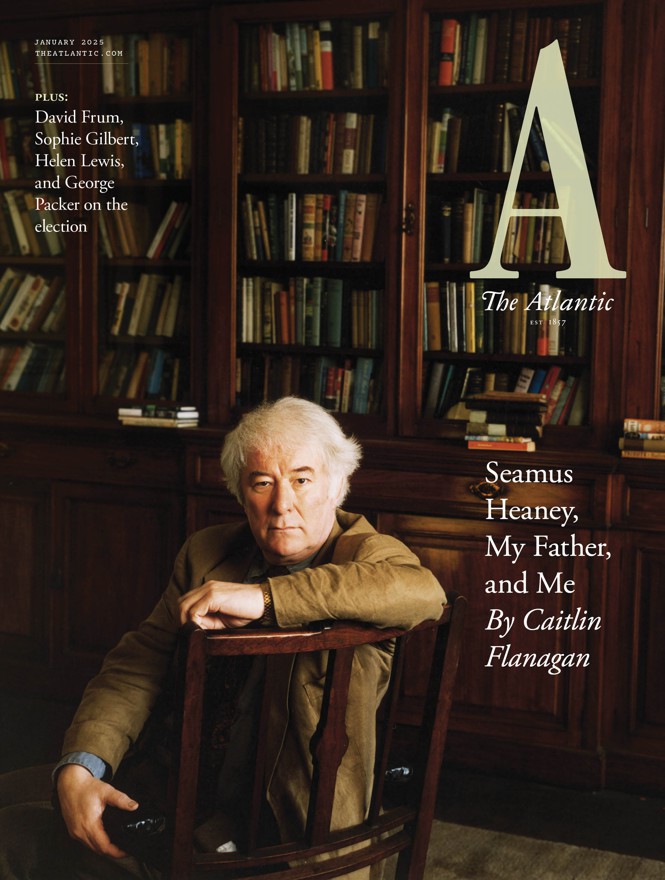

Behind the Cover

In this month’s cover story, “Walk on Air Against Your Better Judgment,” Caitlin Flanagan writes about her relationship with the poet Seamus Heaney. Heaney first met the Flanagan family during a year spent teaching English at UC Berkeley, where Flanagan’s father, Tom, was a professor. Heaney became a second father of sorts, Flanagan writes, and the poet and his work shaped her understanding of the world. The cover image shows Heaney at the Royal Society of Literature, in London, in 1995, months before he was awarded that year’s Nobel Prize in Literature.

— Paul Spella, Senior Art Director

Correction

“The Most Remote Place in the World” (November 2024) stated that, relative to the universe, the plane of the International Space Station’s orbit never changes. In fact, because of the Earth’s oblateness, it does shift over time.

This article appears in the January 2025 print edition with the headline “The Commons.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.