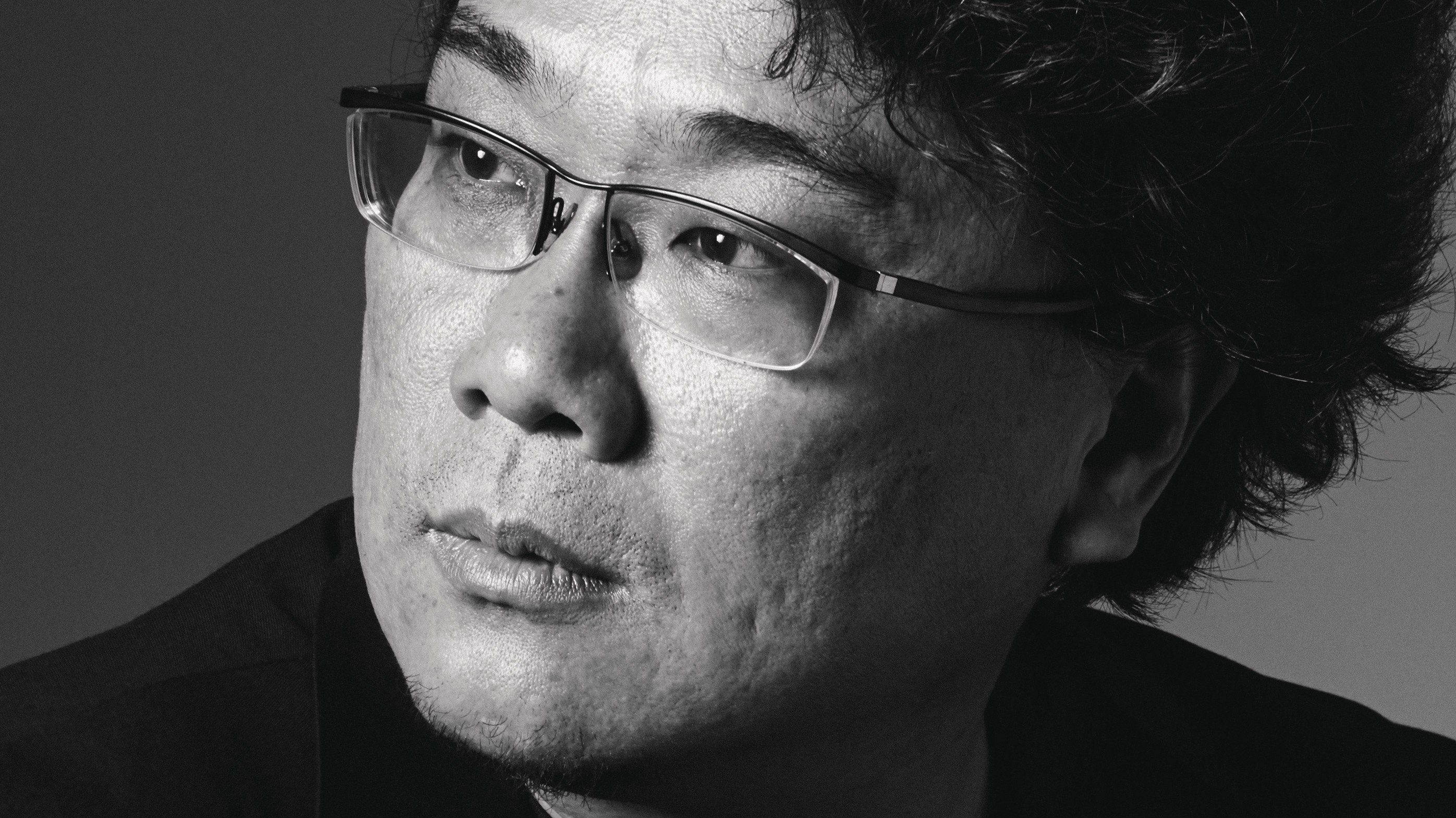

Bong Joon Ho Will Always Root for the Losers

In his new film, Mickey 17, the director brings his preoccupation with classism to outer space.

The director Bong Joon Ho’s new movie, Mickey 17, at first seems like a major pivot from his previous one, 2019’s Parasite. After winning Best Picture at the Oscars for the domestic (if gonzo) Korean black comedy, he’s following it up six years later with a lavish Hollywood sci-fi epic starring Robert Pattinson. But even though Mickey 17 is set in outer space about 30 years from now, its hero isn’t that different from those found throughout Bong’s filmography: a working-class schmo.

Mickey Barnes (Pattinson) lives on a starship, where he’s taken a position as an “expendable.” The vessel’s wealthy owners aspire to colonize the newly discovered, barren planet they’ve landed upon, Niflheim—so they have scientists subject Mickey to tests that will determine how it can be made hospitable. Every time Mickey dies on the job, which is often, the team generates another copy of him with a human-size printer. Then they put him right back to work.

It seems that to Bong, this scenario just sounded like the next evolutionary step of capitalism: one great and terrible leap forward from the contemporary setting of Parasite. When that film begins, the college-aged Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik)—whose family’s attempts to stay financially afloat are central to the grisly and constantly escalating storyline—tries to charm his way into a pizza-delivery gig to help make ends meet.

Ki-woo ultimately doesn’t get the job, but the director imagined what would have happened if he did: He “can get into a bike accident doing [a] delivery, and then immediately Delivery Boy 2 would take his place,” Bong told me in an interview (alongside his longtime interpreter, Sharon Choi). “There’s this endless train of delivery boys that can take his place. Three, four, five, six.” That cycle never comes to pass in Parasite, but its plausibility resonated with Bong when he was approaching Mickey 17: “His job’s not as extreme as dying, but he is just as replaceable, and I thought that really connected to Mickey’s situation.”

[Read: Mickey 17 is strange, sad, and so much fun]

Although Mickey initially sees being an expendable as a rare chance to escape his lackluster life on Earth, he comes to realize that the goal is to test his ability to survive—whether it’s against exposure to harsh environments, unknown viruses, or even floating into space and removing his gear. The cloning process ensures that even death won’t end Mickey’s fatal pursuit; he’s like a more literal version of Parasite’s hypothetically infinite delivery boys.

Bong was “immediately drawn” to the protagonist when reading the novel upon which the film is based: Mickey7, by the author Edward Ashton, which the director received when it was still a manuscript. (“I thought the number had to be a bit bigger,” he said regarding the title change.) “He’s like the powerless-underdog character type that I always love,” the director explained. “Things don’t work out for him. He doesn’t get help from society or the country. He’s kind of this loser-type protagonist.”

Mickey’s circumstances can be blamed, in part, on his high level of debt. Class consciousness drives nearly all of Bong’s features. Take Snowpiercer, his previous full-fledged sci-fi effort, which was also his first to be shot in English: It imagines a postapocalyptic future where all of mankind lives on an endlessly moving train. The poorest passengers toil away in cattle cars at the back. Parasite’s portrayal of these upstairs-downstairs dynamics is even more overt; the members of the struggling Kim household, who live in a basement-level apartment and juggle odd jobs, alight on a crafty employment scheme after encountering an ultra-wealthy family.

[Read: Parasite and the curse of closeness]

Meanwhile, Mickey is the most exaggerated example of the have nots imaginable; his life has been deemed meaningless by the upper-crust owners of the ship and their staff, who have no misgivings about using him as their sentient crash-test dummy. Every time Mickey dies in the name of their colonialist dreams, he experiences true suffering. Then he reemerges in shuddering jolts from the printer, like a giant, fleshy sheet of A4 paper. Sometimes, his new body nearly hits the ground, sliding out of the machine without anyone there to catch him.

For all the grand scale of Mickey 17’s dystopian setting, Bong sought ways to keep it feeling grounded. He wanted the spaceship in which Mickey and the other intergalactic travelers live to feel mundane and industrial; Niflheim, meanwhile, is a barren, frozen hell populated only by giant, buglike aliens. “This film feels like a story that takes place in a back alleyway, filled with pathetic human beings,” Bong told me of his depiction of the interstellar expedition. “It’s probably the first sci-fi film in history to have a shot where someone is squeezing their pimples,” he said, adding that “it’s almost like we can hear the characters mumbling to themselves.”

The utilitarian environments bring to mind those of Ridley Scott’s Alien and John Carpenter’s The Thing—two other sci-fi epics focused on ordinary people who are thrust into some extraordinary circumstance. Alien is an especially relevant touchpoint, as one of the earliest blockbusters to present toiling away in the cosmos not as an adventure but as a gig like any other. An initial conflict, before the eponymous evil creature even arrives aboard, revolves around whether investigating a distress signal is part of the crew’s employment contract. In Alien, “when we see the monster explode out of John Hurt’s chest, the whole atmosphere of that table, it always really stuck with me,” said Bong, explaining that “even within the spaceship, there’s a certain hierarchy—and so it’s blue-collar workers all together.”

The director similarly used his film’s futurist trappings to dial up the social examinations to surreal, even comical proportions. The chief villains are Mickey’s humorously flamboyant bosses: Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo), a preening politician with delusions of grandeur, and his status-obsessed wife, Ylfa (Toni Collette). The couple’s brutal treatment of Mickey contrasts with their interest in populating a new world. “Humans will always be evil, as well in the future, and even when we make our way to space,” Bong told me with a chuckle.

[Read: Parasite won so much more than the Best Picture Oscar]

But Mickey’s experience with the Marshalls is a particularly cynical vision of humanity. “He’s constantly being printed out and sent out to all these dangerous missions,” Bong said, “but no one feels guilty about it, because they’re like, ‘Oh, that’s his job. His job is to die.’” Pattinson’s performance makes this horrifying lack of remorse legible. The actor affects a Looney Tunes–esque voice—which helps illustrate what a pushover Mickey is—but he also physically communicates how Mickey is carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. Bong referred to Mickey as “a character who finds himself in miserable circumstances, has zero self-esteem, and makes the same mistakes over and over again.” The director told Pattinson that he needed a voice befitting that description: “Obviously it can’t be like a Batman tone.”

Pattinson has never been afraid of big, goofy swings. Watching Mickey 17 reminded me of his turn in the 2019 historical epic The King, playing the dauphin of France, the oozingly pretentious son of King Charles VI. But the actor’s wildly diverting performance as Mickey was a huge risk in a movie whose mood is otherwise chilly. Bong said that “those 100 percent serious, weighty sci-fi epics” that a movie like Mickey 17 could resemble aren’t to his taste, however. “I need to somehow find cracks to infuse with humor,” he explained—like Pattinson’s seemingly mismatched approach.

He also found plenty of chances in the story’s first big twist—when an accident that leaves the 17th iteration of Mickey alive means that another Mickey (number 18) begins to coexist alongside him. Mickey 18 is meaner and more somber, allowing Pattinson to try out a completely different persona. This storytelling opportunity was also one reason Bong upped the character’s death count from the source material, searching for a more thematic number. “Once Mickey 18 appears, 17 goes through a journey of growth,” he said. “You can say that Mickey 17 is a coming-of-age film. And if you think about 18, a lot of societies, that’s when you become an official adult.”

The coming-of-age comparison is apt: Mickey 17 came to fruition as Bong stood at something of a crossroads in his career. Although he insists that the production was a smooth process, despite the release date shifting a few times, six years may seem like a long wait for his follow-up to Parasite. But the director admitted that the furor of that movie’s awards campaign—which culminated at the Oscars in February 2020—and the subsequent onset of the coronavirus pandemic were overwhelming. Adjusting to the pressures of newfound global fame can be a steep and isolating challenge, and that’s without the world locking down at the same time. “I would just remember coming back home for the first time in a while and just holding my puppy in my arms,” he said of the post-Oscars period. “It felt like we were in this strange vacuum state.”

Mickey 17 does seem like the kind of film to spring from that mindset. It’s bleak and intimate, but it’s also not without fits of puppy-cradling whimsy. “I just feel a lot of joy in coming up with these elements that are so not sci-fi in a sci-fi film,” Bong said. “As much as I love the genre, I always have this desire to betray it at the same time.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.