Chuck Schumer Is Cautious For a Reason

What the Senate Democratic leader’s new book about anti-Semitism explains about his political choices

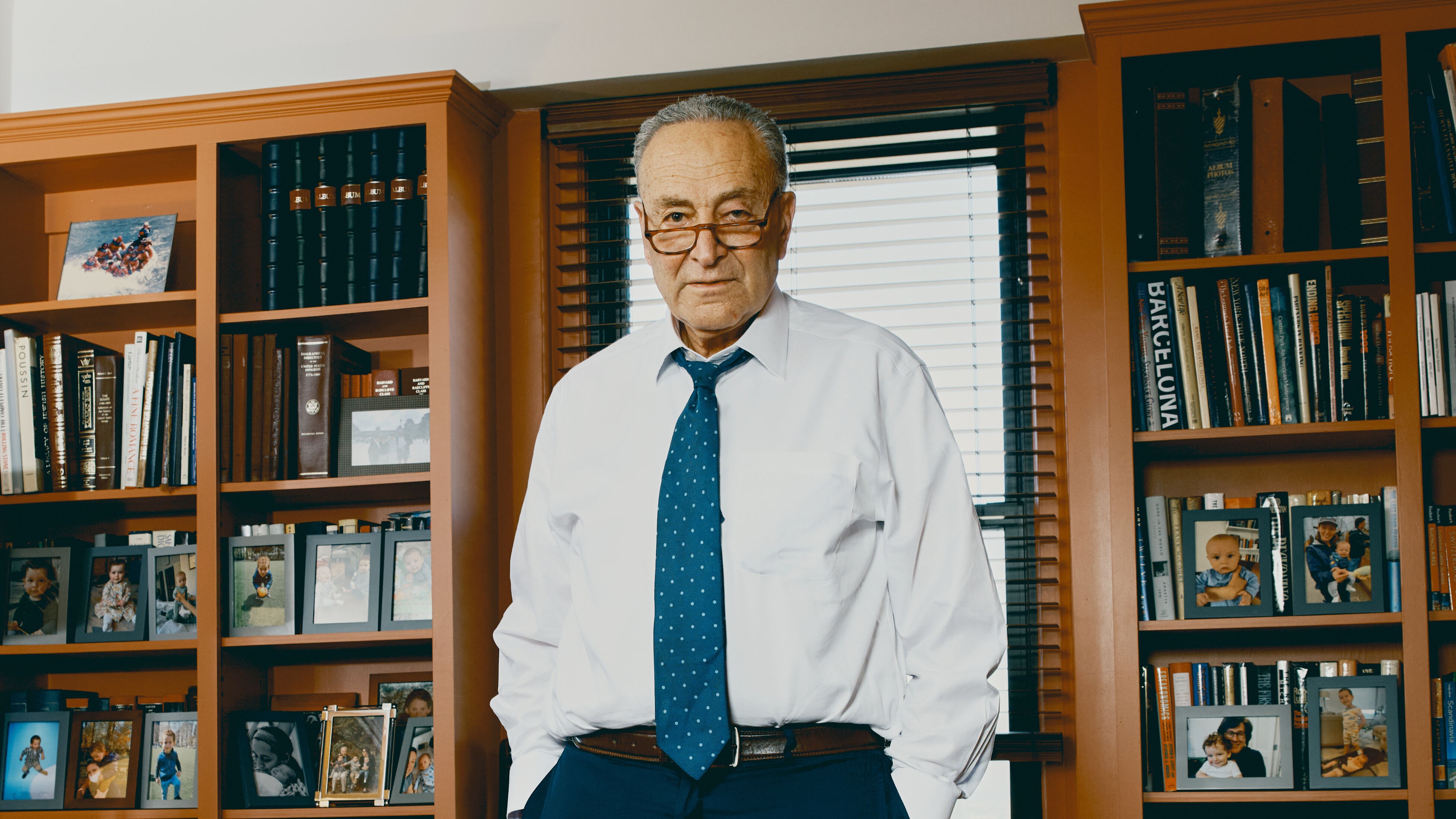

When I walked into Chuck Schumer’s Brooklyn apartment, he was puttering around in his socks. This wasn’t household policy, the 74-year-old Democratic Senate minority leader assured me, so there was no need for me to shed my shoes. But, as a gesture of hospitality, he asked, “Do you mind if I keep mine off?” I didn’t seem to have any actual say in the matter, and so minutes later, we were lounging on the L-shaped sofa in his study, as he discoursed on the color of the walls—call it terra-cotta—that he told me that he really likes, but his wife, Iris, doesn’t.

He had invited me over because there was a hole in his schedule. This was supposed to be the week that he embarked on a multicity tour for his new book, Antisemitism in America: A Warning. The launch was going to be his literary bar mitzvah, where he would bask in the glory of publication. Schumer had poured himself into the project, forcing himself to write intimately about his career, his faith, and his actual bar mitzvah, an event that had come to feel like an omen. Then, as now, the outside world trampled his big moment, and Schumer disappointed loved ones at the very moment he hoped to reap their praise.

As he tells the story, he was scheduled to become a man, in the eyes of the Jewish community, on November 23, 1963—a case of terrible timing, because Lee Harvey Oswald killed the president a day earlier. Even though nobody was in the mood to celebrate anything, his family plowed ahead with the event. And in front of a mournful congregation, Schumer choked. He humiliatingly fumbled through his Torah portion and had no fun at the party that followed. His abiding memory of the day is his father arguing with the caterer to recoup the costs for the after-dinner drinks that never were served.

[From the April 2024 issue: The golden age of American Jews is ending]

Similarly inopportune timing has wrecked the launch of his book. Days before its publication, he announced that he would be supporting a Republican continuing resolution that would prevent a government shutdown. The decision was wildly unpopular with his party’s rank and file, who accused him of squandering the Democrats’ last remaining source of leverage over the Trump administration.

On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart mocked him: “Senator Schumer, no disrespect, but you are a disgrace to Jewish stereotypes about financial negotiation.” Outside Schumer’s Park Slope apartment, on seemingly every mailbox and street sign, there were posters with his photo that read, Missing Backbone … If Found Contact Charles Schumer.

Schumer’s security team began to track specific threats against him. They worried that the furor over the shutdown would create a wave of protests that would test their ability to safeguard him. So Schumer accepted advice that he postpone his tour for a more placid moment in the indeterminate future.

With newfound time on his hands, Schumer and I began to kibitz. He splayed on his sofa, tucked his stocking feet under his knees and propped his head on his hand, striking a Cleopatra pose. He badly wanted to talk about his neglected book and not the continuing resolution. But I began to realize that two subjects were, in fact, woven together. The book is unintentionally a political self-portrait. Schumer’s Jewish identity is at the core of his beliefs: that the viability of public institutions should be defended at all cost; that the fragility of Jewish existence, and of democracy, demands that he resist emotionally satisfying gestures, if they ultimately risk damaging those institutions.

Few American politicians are more unmistakably Jewish than Chuck Schumer. Soon after he joined the House of Representatives in the early 1980s, he recalls in the book, a woman in Queens rushed up to him: “You have more courage than any of the other members of Congress.” Schumer didn’t just take the compliment. He wanted to know why she was lavishing him with such praise. “You’re the only one who had the courage to wear a yarmulke,” she told him. To disabuse her of that idea, he bent down to show her “the appetizer-plate-sized bald spot”—his words—that she had confused for a skullcap.

Despite the expectations Jews might have had for him, he didn’t define himself that way. He told me, “I was always proudly Jewish, but I never emphasized Jewishness. When I ran for the Senate, I was really worried. How would these upstate people react to me?” (Perhaps he need not have worried; he defeated the incumbent, Alfonse D’Amato, after an only-in-New-York controversy over whether the Republican senator had called Schumer a putzhead, a riff on the Yiddish slang for penis.)

Decades passed, and his cautious attitude didn’t change. But then, on October 7, 2023, Hamas attacked Israel, and Schumer felt a new sense of responsibility. No Jew in American political life had ever held the power he then possessed. (The Democrats held a majority in the Senate, so he was running the chamber.) Witnessing the outpouring of anti-Semitism on the left, which focused its harshest criticisms on Israel rather than Hamas, Schumer felt compelled to fully embrace his identity, in all the ways he’d historically resisted.

His decision to expend so much time talking about anti-Semitism didn’t please his aides, who urged him to steer clear. On the political merits, his staff had valid arguments. Schumer planned on chastising the left, attacking members of the party he led. He writes that he was determined to make a fervent case for Israel, despite that country’s diminishing popularity among die-hard Democrats. He recalls telling himself, “You are no great Jewish sage or scholar, you are no King Solomon or Maimonides or Elie Wiesel, but for better or for worse, you are here, and you ought to try to do some good.”

[Read: Trump’s crocodile tears for the Jews]

What’s interesting about the book was that writing it didn’t just inspire him to more strongly identify himself as a Jew, but also prodded him to consider the Jewish roots of his approach to politics. (Full disclosure: At several points in his book, Schumer approvingly quotes an essay I wrote about Judaism in America.)

He began to think back to his time as a student at Harvard, in the late ’60s. Even though he protested against the Vietnam War, just like his classmates, he didn’t like how they took over buildings in the name of the movement. In the book, he recalls, “I was never going to be on the side of the radicals. I was going to take my own path and try to work through the system and get results, even if it meant compromise and concession from time to time.”

Schumer’s recollections of that era mirror his current difference of opinion with his base over the government shutdown. “Even if I failed and they shut me down and some of them told me I was a sellout,” he writes, “I would try to convince them to seek progress with me on the issues we both cared about. It was more of a human principle and less of a political one.”

When I brought up this passage, he told me that this human principle grew subconsciously, at least in part, from his Jewishness. Schumer viewed the preservation of American institutions as a matter of Jewish preservation, because those institutions were equipped to protect religious minorities. They were the source of America’s exceptional tolerance of Jews: “One of the great things about America is we’ve always had these norms, and we don’t want them broken,” he said, “because they protect all Americans, but particularly Jewish people, who have been so subject to problems and vilification through the centuries.”

In the past few weeks, many of the American institutions he reveres, and the constitutional system designed to insulate them, have come under intense pressure that they might not withstand. And, apropos of Schumer’s book, Trump has created conditions for anti-Semitism to flourish. The president has surrounded himself with a disturbing collection of appointees with records of repeating old canards about Jewish power.

As Schumer explained the president’s attitude toward Jews, he told me a story that he left out of the manuscript: After Trump came to office in 2017, he invited congressional leaders to meet with him. “There’s a spread in the White House, and the first thing he says to me is, ‘Chuck, have a pig in the blanket. They’re kosher.’ First, I’m not sure they were kosher. Second, what was he thinking? He’s a Jew.” (I reached out to the White House for comment on this anecdote and have not yet heard back.)

Trump, in his autocratic mode, seemingly ascribed himself the power to determine what’s kosher and not. And more than that, he’s determined that he has the ability to determine who’s a Jew and not. Last week, he bizarrely declared that Schumer “is not Jewish anymore.” In the words of the president of the United States, “He has become a Palestinian.” (“Don’t tell my mother,” Schumer told me in response.)

The president was assuming a posture that rarely ends well, in which the regime separates the good Jews from the bad ones. By deeming them religious reprobates, the regime is signaling that they are the acceptable ones to abuse.

Does Schumer’s institutionalism have the fortitude to resist Trump? When he voted to prevent the government shutdown, he was acting not just on instinct, but on intelligence gleaned from Republican sources, who told him that the administration was baiting the Democrats into shutting down the government. The White House had a plan for how it would use the cover of a shutdown to accelerate its assault on the government, while pinning blame for the crisis on the Democrats.

But Schumer was also acting on instinct. As he remembers the radicals at Harvard, he says, “I saw how their zeal and fury led them to be not only demeaning to other students but disruptive, which was ultimately counterproductive. They turned too many people off.” In the end, he was right, and they were wrong. The backlash against antiwar protest helped to doom ’60s liberalism, ending the Great Society and stalling the advance of civil rights.

As I sat with him on the sofa, I received an alert from Axios: “Schumer faces growing House Dem calls to step down.” But he seemed unfazed. “The higher you go on the mountain, the more fiercely the wind blows,” he told me. “The only way to protect yourself from these fierce winds is to have your own internal gyroscope. That’s what motivated me in how I voted.” The same instinct motivated him back at Harvard, he said. “I hated the Vietnam War, but I felt there was a right way.” He was now lying on his back, his feet propped up, the knot of his tie dangling at his torso, a man either oblivious to the revolt brewing against him, or at ease with his own political choices.