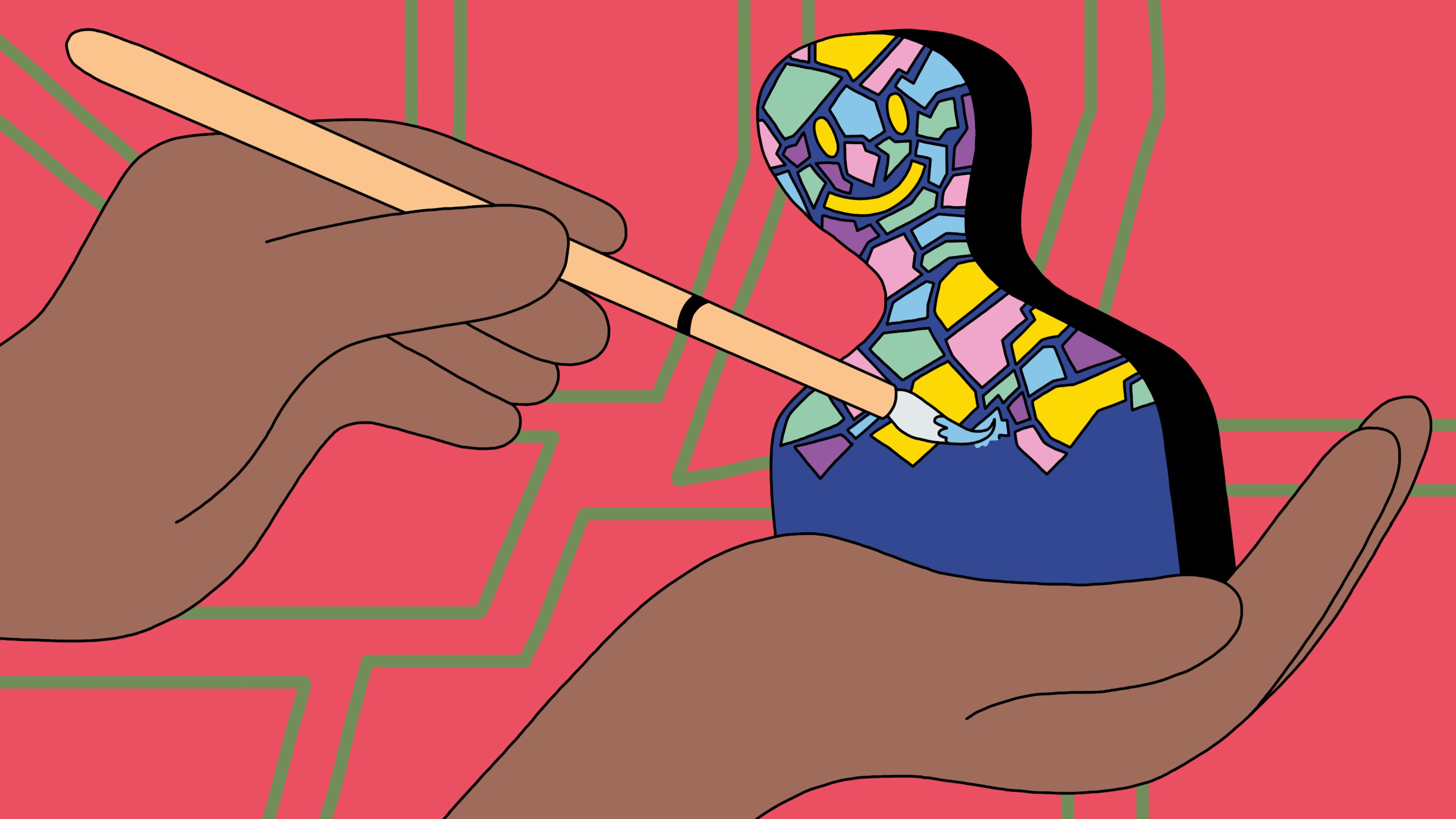

How to Avoid the Creative-Narcissist Trap

Artists can be self-obsessed jerks. But you can get in touch with your artistic side without falling into that trap.

Want to stay current with Arthur’s writing? Sign up to get an email every time a new column comes out.

As a behavioral scientist with a long interest and background in the arts, I’ve always been fascinated by the 20th-century Catalan surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. Many regard him as a genius, but he is at least as famed for his eccentricity as his art. He claimed, for example, to be a reincarnation of the Spanish mystic Saint John of the Cross, in whose guise he could “remember vividly,” he said, “undergoing the dark night of the soul.”

Where disagreement over Dalí does occur, it centers on whether his madness was real or feigned. Those who believe the latter argue that he was a compulsive liar who manipulated people with his outlandish impostures to gain success. Why might Dalí practice deception in such a bizarre and audacious way? Perhaps a compulsion to deceive was not in spite of his extraordinary creative powers, but actually because of them.

“Imagination,” wrote the French philosopher Blaise Pascal in the 17th century, “is that deceitful part in man, that mistress of error and falsity.” To which he added, “I do not speak of fools, I speak of the wisest men.” It sounds as if Pascal had a bone to pick with artists; in fact, he was ahead of his time in divining what, centuries later, researchers found evidence for: an organic link between creativity and corrupt behavior.

What Pascal missed was that creativity does not inherently lead to unethical conduct. Creativity is a particular form of power: the power to see new possibilities more clearly than others do. And, like any other power, creativity is commonly misused when not deployed in the service of others. Fortunately, there are ways you can use your creativity that truly enhance your life and others’.

[Arthur C. Brooks: Mindfulness hurts. That’s why it works.]

Researchers have looked carefully at whether highly creative people tend to be more or less ethical than the population average. At first glance, the evidence is mixed: Some studies show a positive relationship, while others show no association. But closer examination of that apparently conflicting finding tells a different story. Studies showing no connection between creativity and unethical conduct are based on self-reporting surveys, whereas the positive correlation comes from objective measures, such as observation of unethical behavior by other people or in experiments. In other words, creatives say they’re not unethical—surprise!—but are observed to be so by others.

One example of this pattern is a 2013 psychological experiment in which college students were offered class credit for participation. They were given a test of their creativity in which they had to come up with one word that would associatively link three random other ones. (For instance, if the prompt words were falling, actor, and dust, a person might connect them with the word star.) They were then asked to rate their own integrity. These exercises were followed by a tedious survey that they had to complete to get the credit. But the survey was designed in such a way that participants could see how to skip part of it undetected (so they assumed), but claim they had fully done it. The cheaters on the survey registered as much more creative in the word test than the non-cheaters, yet the cheaters scored their own integrity at roughly the same level as the non-cheaters rated theirs.

Creativity and unethical behavior tend to be most strongly correlated when, as one 2017 study showed, rules are vague and hard to enforce, rather than clear and unambiguous. This can occur in romantic relationships where expectations about exclusivity and fidelity are assumed but not spelled out; differing assumptions can lead to, well, creative ambiguity. If an artist or a musician has been unfaithful to you, this might explain why. (Indeed, poets and artists tend to have more sexual partners than the population average.) Lack of clarity in the mind-numbing million words of the Internal Revenue Code may also explain the problem of “creative accounting” in some businesses’ tax declarations.

[Read: Mapping creativity in the brain]

If, as I argued above, creativity is not just a gift but also a form of power, then—just as “power tends to corrupt,” as Lord Acton said—humans can be tempted to misuse their creativity. I could argue with Lord Acton, in fact, over whether power is inherently corrupting, but I know, from the extensive research on the topic, that holding power over others can certainly be correlated with unethical behavior such as cheating.

One personality trait that links creative power and dishonesty is narcissism. In Dalí’s 1942 autobiography—which a disgusted George Orwell later called “a strip-tease act conducted in pink limelight”—the surrealist showman proudly diagnosed himself a narcissist, a judgment that anyone with even a passing familiarity with his life will find hard to refute. Indeed, narcissism is strongly correlated with many measures of creativity, as well as with unethical behavior.

People who are self-absorbed find that this quality helps them tap into their creative potential. But this very self-absorption also tends to make them selfish and willing to cut ethical corners to benefit themselves. That is certainly a risk for people with creative power. But for those who can resist their narcissistic impulses and use their creativity for the good of others, the result is almost bound to be ethical.

One way to ensure that you’re using your creative power ethically borrows an entrepreneur’s standard technique by subjecting every decision to a checklist of conditions. For example, a small start-up might stay focused on its mission by making sure that any new opportunity is: 1) sustainable; 2) scalable; and 3) potentially profitable. In an analogous way, I use an ordered algorithm for my own creative work (including this column) to ensure that it meets my ethical standards. It must: 1) glorify the divine; 2) uplift others; and 3) be interesting to me. If a given piece of work meets only criterion 1, or 1 and 2, I might still go ahead with it; but if it does not achieve 1 and 2, I won’t proceed under any circumstances.

The idea of setting those ordered criteria is to prevent me from ever engaging in creative work that is snarky, hurtful, or indecent. I recommend it: Even if you don’t see yourself as “a creative,” you can use the approach to apply your own algorithm of ethical service and love for others.

[Read: Gaudí’s Basilica: Almost finished after 132 years]

Dalí used his prodigious creativity to amplify his own prestige, fame, and wealth. His life and work were marked by egotism, manipulative behavior, and ruined relationships. By all accounts, that did not end well: By the time of his death, he was mired in depression and alienated from others. Despite his evident genius, Dalí is not someone to emulate in your own creative endeavors, artistic or otherwise.

A model I prefer is Dalí’s Catalan forebear, the modernist architect Antoni Gaudí, who designed Barcelona’s stunningly beautiful Sagrada Familia basilica. A deeply religious Catholic, he dedicated this and his other works to glorifying God and lifting up the people who saw and used them; the Vatican is considering the case for Gaudí’s canonization.

Even Dalí admired and praised Gaudí’s extraordinary creations—but, being Dalí, he couldn’t resist injecting a nasty little jab inside his praise: “Those who have not tasted his superbly creative bad taste are traitors.”

In your creative endeavors, be a Gaudí, not a Dalí.