It Isn’t Country Music: The Real Reason CMA Awards’ Snub of Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ Wasn’t ‘Racist.’

Ringo Starr has a new country music album set for release on Jan. 10, and the legendary ex-Beatle appears to have recorded an LP that... Read More The post It Isn’t Country Music: The Real Reason CMA Awards’ Snub of Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ Wasn’t ‘Racist.’ appeared first on The Daily Signal.

Ringo Starr has a new country music album set for release on Jan. 10, and the legendary ex-Beatle appears to have recorded an LP that has more of a traditional country music sound than almost anything playing on contemporary country radio today or, for that matter, a good many of the songs feted Wednesday night at the 58th annual Country Music Association Awards.

And the first two tracks Starr has released from “Look Up” are certainly more country than anything on Beyoncé’s overhyped, pretend-country album “Cowboy Carter” released in late March, which was deservedly snubbed by the CMA.

Perhaps not surprisingly, however, Beyoncé’s shutout has spawned baseless accusations of “racism”—the new last refuge of scoundrels. (More on that in a bit.)

Beyoncé accepts the Innovator Award from Stevie Wonder at the 2024 iHeartRadio Music Awards in Los Angeles on April 1 after the release of her album “Cowboy Carter.” (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

To this old-school country music purist, Starr’s foray into country music is a welcome development, especially after listening to the “Hot 30 Weekend Countdown” on “The Highway,” Sirius-XM’s contemporary country channel, to get a sense of what country music today has become: It’s largely indistinguishable from jangly pop and rock, albeit in cowboy boots and ten-gallon hats and sung with a “y’all” affectation. For the most part, steel guitars, banjos, and mandolins are missing.

My lament at the watering down of authentic country music reflects my personal Sturm und Twang. It stems from my decades-long love of twangy, old-school country music (the kind drenched with fiddles and steel guitars) that dates back to my senior year in high school, when I took a Greyhound bus 115 miles to see Charley Pride, Ronnie Milsap, and Gary Stewart in concert in Bangor, Maine.

Two tracks from Starr’s forthcoming album were made available in mid-October for downloading ahead of the full LP’s release—perhaps strategically in hopes of getting mentioned at Wednesday night’s CMA awards show cohosted by singers Luke Bryan and Lainey Wilson and NFL great Peyton Manning. That didn’t happen, but “Cowboy Carter”—released much earlier—didn’t get any recognition, either—much less any award nominations or trophies. (If it’s any consolation to Queen Bey, 91-year-old country legend Willie Nelson’s new album, “Last Leaf on the Tree,” also was not referenced at all.)

Beyoncé’s deserved CMA shutout has less than nothing to do with her being black, though some in the legacy media and on social media alike are implying it’s due to—you guessed it—racism.

Occam’s razor offers a less-kneejerk explanation: One could stretch the definition of country music to the breaking point, and “Cowboy Carter” would still not qualify as country. As a former part-time DJ on a country music station much earlier in my career, I know C&W when I hear it, and I didn’t hear it on “Cowboy Carter.”

What makes it more interesting, however, is the 2024 CMA awards’ snub came less than two weeks after the Recording Academy on Nov. 8 unveiled nominees for the 67th annual Grammy Awards, to be presented Feb. 2, and the Grammy nominators appear to have had an “eargasm” over “Cowboy Carter.”

As the music industry trade publication Billboard magazine noted on Monday, “the differences in the two institutions’ approaches to country are even more glaring than in previous years. Houston native Beyoncé is the clearest example of the dichotomy. Her country-hybrid album, ‘Cowboy Carter,’ and seven of its tracks amassed 11 Grammy nominations, making her the leading finalist in the entire contest. Her portfolio includes entries in each of the four country-specific categories: best country song (‘Texas Hold ’Em’); best country album (‘Cowboy Carter’); best country solo performance (‘16 Carriages’); and best country duo/group performance (‘II Most Wanted,’ featuring Miley Cyrus).”

As a pop and R&B record, “Cowboy Carter” has sold several million copies, but Beyoncé shouldn’t win any country Grammys for it.

The profanity-laced 17-track “Cowboy Carter” also includes a cover of Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” with its lyrics gratuitously rewritten, as well as two duets with Parton and two more with Nelson. Still, none of it warrants treating “Cowboy Carter” as a country music album for awards purposes—or any other purpose, for that matter.

None of its three Grammy-nominated singles even remotely qualifies as country music—which, I suppose, tells you all you need to know about the Grammys nominating committee’s apparent disdain for genuine country.

By contrast, Starr’s first two releases from “Look Up”—“Time on My Hands” and “Thankful,” the latter featuring bluegrass virtuoso Alison Krauss—certainly offer up a more traditional country sound than “Texas Hold ’Em,” “16 Carriages,” or “II Most Wanted.” “Thankful” is smothered with steel guitar, whereas “Cowboy Carter” wouldn’t know a steel guitar if one fell in his lap.

Music writers and others in their liberal echo chamber—reflexively and without evidence—suggest that the resistance by country music purists (like me) to Beyoncé’s non-country country music is somehow “racist.” They typically point to the minuscule number of black artists in the field, notably Darius Rucker, Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, and Shaboozey. But that dearth is due less to “racism” on the part of the country music industry and its fandom than it is to career self-selection. Simply put, if more black singers pursued traditional country music careers, they would be welcomed in Nashville and beyond with open arms.

Shaboozey—who had an enormous hit single, “The Bar Song (Tipsy)”—didn’t win either of the CMA awards he was up for, and that, too, was branded by his fans as racism on the part of the association, The New York Post reported.

While “Tipsy” was in fact far closer to real country music than “Cowboy Carter,” it was as if the CMA judges were somehow obligated to give him one or both trophies. Newsflash: There were dozens of other nominees Wednesday, virtually all of them white, who also went home empty-handed.

The country music “racism” charge is—and always has been, for decades now—a baseless canard, as Pride proved definitively across his 50-year career. He logged close to 80 singles on the country charts, with 52 of them making the Top 10 and 29 reaching No. 1, beginning in 1966.

Further belying Shaboozey fans’ false accusations, Pride during his career won four CMA Awards: Entertainer of the Year in 1971; back-to-back Male Vocalist of the Year Awards in 1971 and 1972; and the 2020 Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award.

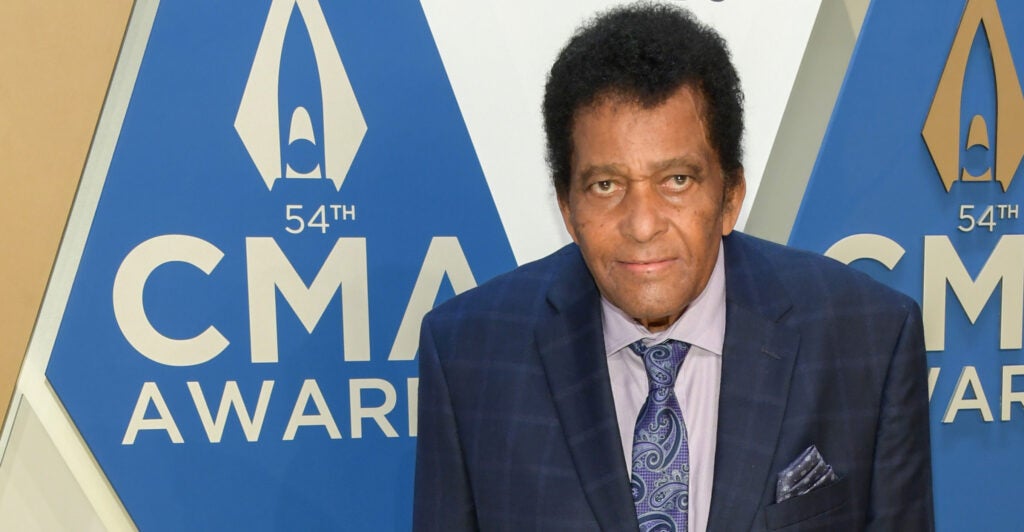

Legendary country singer Charley Pride attends the 54th annual CMA Awards on Nov. 11, 2020, in Nashville, Tennessee. He died a month later on Dec. 12, 2020, at age 86. (Jason Kempin/Getty Images)

But I digress, again.

Another thing that distinguishes old-school country music from today’s is this: Pride and most of the other big names in old-school country music had immediately recognizable voices. Within a few seconds of a song being played on the radio, you knew instantly who was singing—be it Merle Haggard, George Jones, Johnny Cash, Buck Owens, Conway Twitty, or countless others. In like fashion, Loretta Lynn’s and Tammy Wynette’s voices wouldn’t be mistaken for those of, say, Crystal Gayle (Lynn’s kid sister), Emmylou Harris, or Donna Fargo. Even the groups back then—the Statler Brothers, Alabama, and the Oak Ridge Boys (the latter among the awards presenters Wednesday night)—all had unmistakable sounds.

Neotraditionalists George Strait and Alan Jackson, who burst on to the country music scene in 1981 and 1987, respectively, captured the angst I feel with their 2000 duet “Murder on Music Row.” It lamented the compromising, by the execs in the record company C-suites, of the distinctive honky-tonk sound in search of broader audiences—and, more importantly, revenues. (Strait—who won this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award—has sold the second-most albums ever by a country singer, behind only Garth Brooks, proving that kind of compromise wasn’t and isn’t necessary.)

But this week, listening to that Top 30 countdown of today’s country music, I was struck by how most of today’s country artists are all but vocally indistinguishable from one another.

One final observation about the CMA Awards: Whatever else one can say about Jelly Roll and Post Malone, they aren’t really country singers, at least not by traditional notions of the genre. (And by the way, what’s up with their face tattoos? Are they aspiring to become Latin American drug gang members?)

As for Starr, whose country bona fides trace back to his lead vocals on the Beatles’ cover of Buck Owens’ “Act Naturally” in 1964, he will be playing two nights at Nashville’s historic Ryman Auditorium the week after his album drops in January. Maybe “Look Up” will then garner some award nominations from the rival Academy of Country Music at its 60th annual awards ceremony next May 8.

Ex-Beatle Ringo Starr unveils his new country album, “Look Up,” on Nov. 15 in Los Angeles, adding country “starr” to his resume. (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

Until then, I’m going to take the off-ramp from “The Highway” back Sirius-XM’s “Willie’s Roadhouse” channel, where twangy old-school country rules the airwaves and where—to borrow a line from Nelson’s late BFF Waylon Jennings—“Bob Wills Is Still the King.”

The post It Isn’t Country Music: The Real Reason CMA Awards’ Snub of Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ Wasn’t ‘Racist.’ appeared first on The Daily Signal.