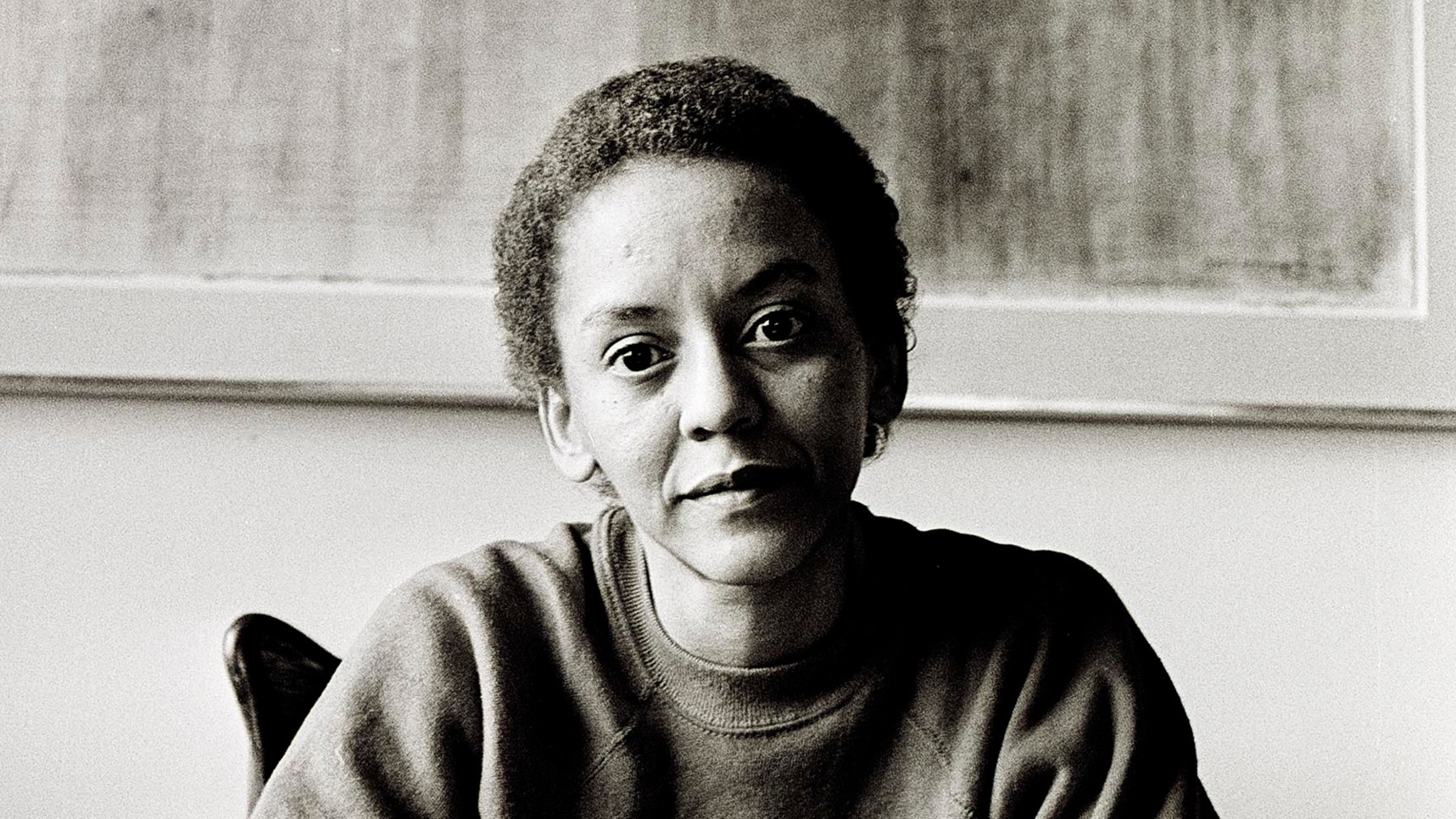

Nikki Giovanni’s Wondrous Celebrations of Black Life

The poet’s work crackled with revolutionary fire but also contained jubilation and gentleness.

In the last years of her life, Nikki Giovanni felt her memory fading. At the beginning of the 2023 documentary Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project, she offered an inventive take on how the loss affected her: “I remember what’s important, and I make up the rest. That’s what storytelling is all about.” Giovanni’s playful reflection on aging and the alchemy of storytelling captured an essential truth about her work. The poet and scholar, who died Monday at 81, was a gifted chronicler of the wonders and complexity of Black life—a talent buoyed by her warm, imaginative approach to both art and social change. To read Giovanni’s poems or hear her speak was to immediately feel her profound care for Black people.

Giovanni understood that Black American cultural history was, in part, the inevitable result of centuries-long oppression—but that it was also the product of constant evolution. Through her prolific writing, activism, and engagement with younger generations, she cultivated a sense of limitless possibility about language and social movements. Giovanni’s earliest works nodded to her expansive vision. Her first book of poems, Black Feeling, Black Talk, was self-published in 1968, when Giovanni was in her mid-20s. By that climactic year, she was already a rising figure in the Black Arts and civil-rights movements, and her poetry crackled with the same revolutionary fire fueling writers such as Amiri Baraka, Audre Lorde, and Ntozake Shange.

Even then, Giovanni was concerned with the tender minutiae of Black American experiences, and her poetry celebrated some of the everyday pleasures that make resilience feel possible. In “Knoxville, Tennessee,” named for the town where she was born Yolanda Cornelia Giovanni Jr., the poet’s vivid imagery conveyed both her childhood delights and the precarity of living in the segregated South. “I always like summer / best / you can eat fresh corn / from daddy’s garden,” the poem begins. At its conclusion, Giovanni gestures toward the desolation left behind after the season retreats, when being warm is reserved for “when you go to bed / and sleep.” By her 30th birthday, Giovanni was regularly publishing poems that tapped into the transformative power of focusing inward as a community—and working through what that meant in practice alongside formidable intellectuals such as James Baldwin.

Decades before intra-community affirmations such as “Black-boy joy” and “Black-girl magic” went viral—and became commercialized—Giovanni drew attention to the persistence of love, jubilation, and gentleness in Black American life. The author was especially adept at conjuring the bone-deep satisfaction of another ephemeral experience: preparing and consuming food that drew on Black American culinary traditions. Like Shange, who published a culinary memoir in 1998, Giovanni saw Black foodways as a vital conduit of diasporic knowledge and connection. An accomplished, self-described “Southern cook” in her personal life, Giovanni also embraced this ethos in poems such as “My House” and “Seduction / Kidnap Poem,” which articulated a cultural consciousness rooted in femininity, and in the care work typically associated with women.

Among the most energizing constants of Giovanni’s writing was her transformation of simple, familiar images into resonant symbols. Just as the bountiful vegetables of her father’s garden disappear by the end of “Knoxville, Tennessee,” the title of “Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day” evokes an inevitable transition. The aging speaker in a later Giovanni poem, “Quilts,” likens herself to “a fading piece of cloth,” eventually landing on the idea that even a frayed old quilt “might keep some child warm.”

[Read: Nikki Giovanni: ‘Martin had faith in the people’]

The poet’s appreciation for the artistic possibilities of community was often expressed in direct contrast to other, more distorted views of Blackness. “Nikki-Rosa,” for example, begins with an ostensible lament—“Childhood remembrances are always a drag / if you’re Black”—and ends with a defiant declaration of the poet’s subjecthood. “I really hope no white person ever has cause / to write about me / because they never understand,” Giovanni wrote in the 1968 poem. “Black love is black wealth and they’ll / probably talk about my hard childhood / and never understand that / all the while I was quite happy.”

Giovanni’s ability to hold on to this perspective, and marry it with a distinct flair for the fantastical, imbued her poems and social commentary with a youthful curiosity well into her final years. Whereas some scholars resign themselves to the rigidity of academia, Giovanni, who was an English professor at Virginia Tech until 2022, remained committed to learning new lessons. Speaking about her 2021 poem “Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea (We’re Going to Mars),” Giovanni recalled her realization that the otherworldly language of space exploration reminded her of the Middle Passage, the brutal voyage that transported enslaved Africans to an unfathomable new reality. “That’s what we do when we put somebody on a rocket. They’re going from Earth into an area that they don’t know—they think they might know, but they’re not sure,” she told Oxford American earlier this year, drawing out the comparison. “And so I thought, Well that’s what Black people have done. And we have survived and thrived and shared a lot of love. We brought a lot of goodness.”