The Government Needs to Act Fast to Protect the Election

Following the Supreme Court’s Wednesday decision, federal agencies can and should resume their efforts to communicate with social-media companies about disinformation online.

The sophistication, scope, and scale of disinformation in this year’s election could be beyond anything the country has experienced before. The federal government will not be able to solve this problem entirely, but because of Wednesday’s decision in Murthy v. Missouri, it will at least be able to work with social-media companies to try.

The legal challenge to the federal government’s efforts on this front began in 2022. The attorneys general of Louisiana and Missouri filed a lawsuit along with several private plaintiffs claiming that the federal government had violated Americans’ First Amendment rights by identifying posts containing false information on social-media platforms, and in some instances asking platforms to take down those posts or to give authoritative information more visibility in users’ feeds. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court said that the plaintiffs did not have standing to file that lawsuit and dismissed the case. (Last December, together with our colleagues at the Brennan Center and the law firm Stris & Maher LLP, we filed an amicus brief in the case on behalf of a bipartisan group of current and former election officials, highlighting the importance of communication between social-media companies and the government.)

[Evelyn Douek and Genevieve Lakier: The hypocrisy underlying the campus-speech controversy]

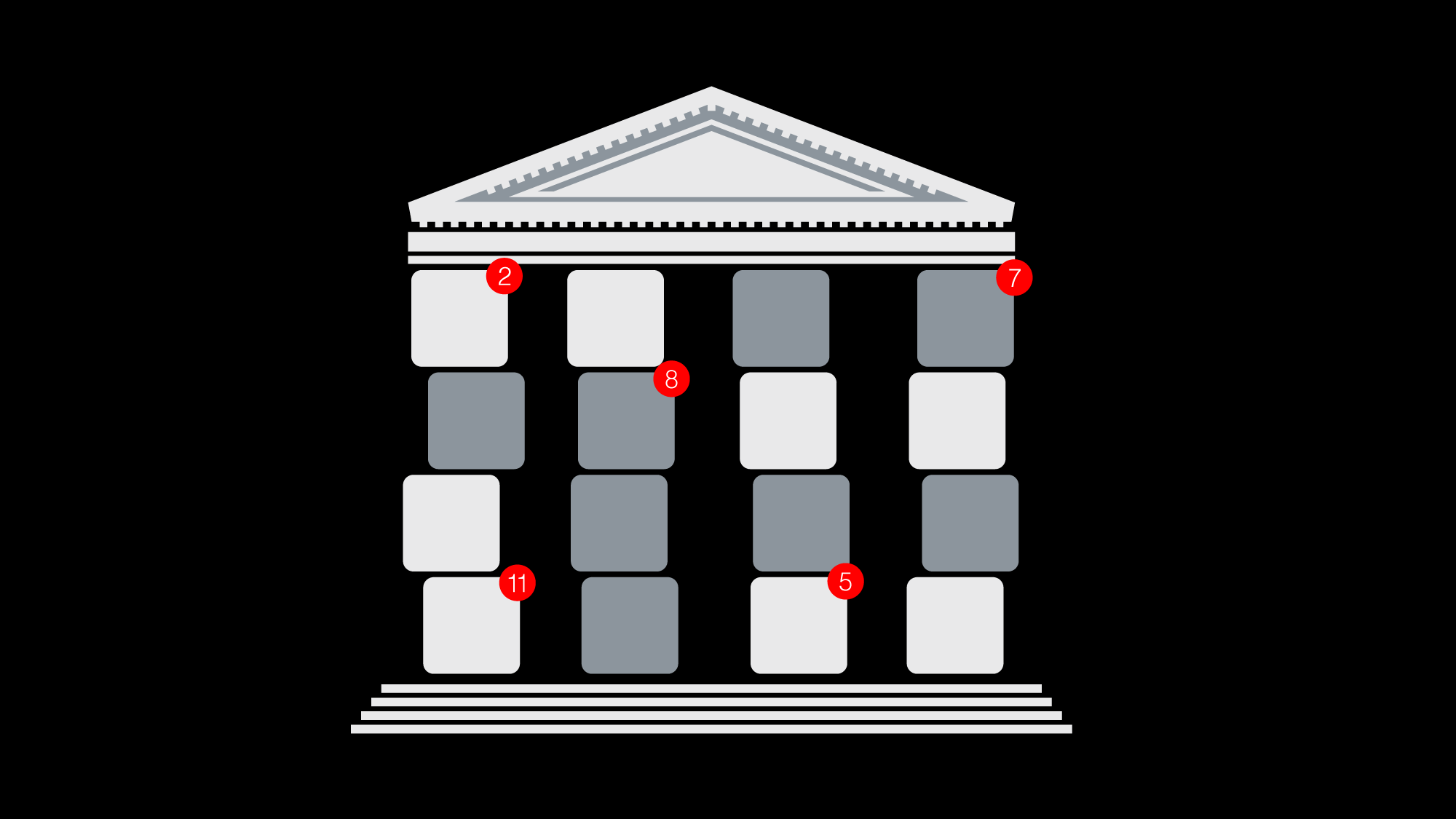

The case should never have gotten as far as the Court to begin with, and great costs were incurred while the case worked its way through the legal system. A sweeping district-court decision in July 2023 stopped federal agencies from communicating with social-media companies, and that ruling was mostly upheld by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals a few months later. As a result, federal agencies with expertise in elections and disinformation stopped sharing their intelligence—about foreign interference efforts, election denialism, and false information on when and where to vote—with social-media companies, a practice that had been common since Russia’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 election. They also stopped sharing accurate information about elections. This came as preparations for the 2024 presidential election were getting under way.

The social-media companies appear to have had a similar response to the lower-court ruling. According to an amicus brief submitted to the Supreme Court by a group of secretaries of state, Meta told a group of state officials in late 2023 that the company was not planning to “facilitate direct communications” between those officials and its platforms. In their brief, the state officials argued that this wouldn’t change unless the Supreme Court acted as it did Wednesday.

With Murthy now dismissed and limited time before November 5, the federal government can and should immediately resume its regular briefings with social-media companies about foreign interference in our elections. Although there are encouraging signs that the federal government is slowly resuming these efforts, they appear limited compared with what was done in prior elections. The government should also, as it has in the past, help connect state and local election officials with appropriate contacts at social-media companies. That way local officials and social-media companies can keep each other apprised of any changes in disinformation they are seeing regarding how, when, and where to vote. And the federal government should drastically increase efforts to inform the American public about foreign adversaries’ operations intended to decrease confidence in elections. The government must also make clear that threatening election officials—and their families and children—will not be tolerated.

Tech companies must step up too, by updating and consistently enforcing their policies on handling election falsehoods. The companies should also restore channels for election officials to report election falsehoods, and amplify accurate information about elections from those same officials.

Murthy was one piece of a larger political and legal effort to silence those calling out election falsehoods and promoting true information. The Murthy decision by itself will not end the effort to undermine our democracy. But it should provide those in government, as well as the private and nonprofit sectors, with the courage and fortitude to do what they can.