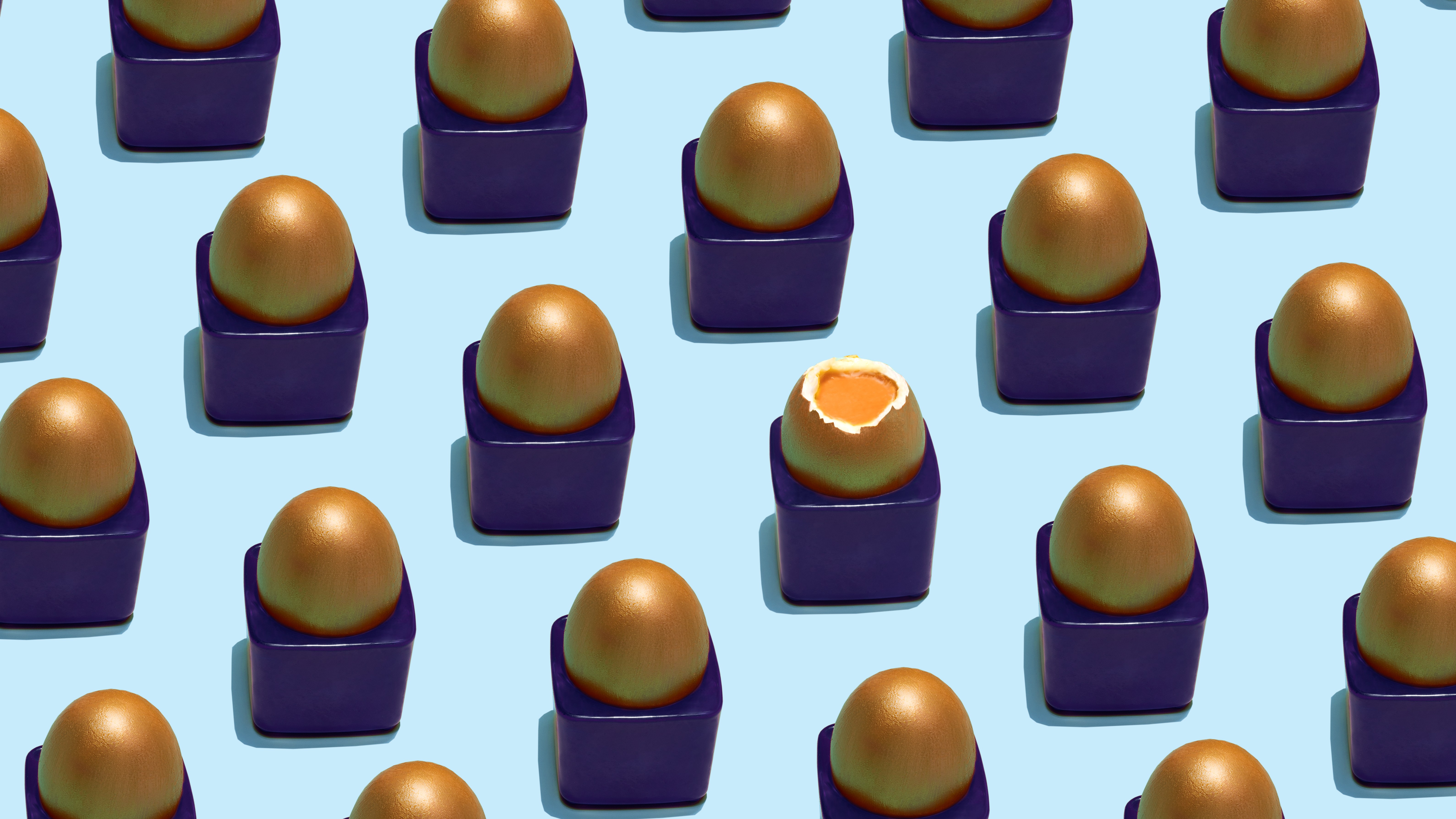

The Logic of Egg Prices Is Getting Scrambled

Restaurants and grocery stores are reaching a breaking point.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

One sign that the egg-cost crisis has gotten dire came in the form of a bright-yellow sticker on a laminated breakfast menu: On Monday, Waffle House announced that it would be adding a temporary 50-cent surcharge to each egg ordered.

Egg prices have risen dramatically as of late. First, inflation pushed up their cost. Then the ongoing bird-flu outbreak led to shortages. On the campaign trail, Donald Trump assured Americans that he would get food costs under control: He vowed last summer that he would bring food prices down “on day one”—a promise he did not fulfill. As egg prices have kept ticking up in recent weeks, Karoline Leavitt, Trump’s press secretary, has blamed the Biden administration for high egg costs, citing the standard, USDA-authorized measure of killing millions of egg-laying chickens that were infected with bird flu (something the previous Trump administration also did). The average price of a dozen eggs in U.S. cities remained below $2 until 2022. Eggs now cost an average of more than $4 a dozen—it’s a lot higher at some grocery stores—and the USDA has forecasted a 20 percent further price jump for eggs in 2025. As a spokesperson for Waffle House said in a statement, high egg prices are now forcing customers and restaurants to make “difficult decisions.”

As egg prices shift, so does the pricing logic that grocery stores and restaurants have long used. For decades now, grocers have helped maintain eggs’ affordable image, even when the amount they themselves spent on eggs was fluctuating. Many stores consider eggs “loss leaders”; they effectively subsidize the cost of eggs in order to draw in shoppers (who, they expect, might then splurge on higher-margin items). This was possible for stores to do because eggs were cheap to produce and readily in supply. Innovations in industrial farming, incubation, artificial lighting (to trick hens into thinking it was morning and time to lay), and carton technology meant that, by the early 20th century, cheap eggs were bountiful in American markets.

But when wholesale costs soar, as they are now, the loss-leader rationale starts to strain. (The cost of a dozen eggs for restaurants and stores is about $7, compared with $2.25 last fall, according to one recent estimate.) A few grocers are keeping egg prices consistent despite rising costs, but many more have started passing high prices over to shoppers. Eggs are also ingredients in lots of grocery items, such as baked goods and salad dressing—so those may see price increases too.

As for restaurants, when the cost of a single item goes up, they are generally willing to absorb it, with the hope that the price will soon go down and perhaps another item will be cheaper the next month, Alex Susskind, a Cornell professor who teaches courses in food and beverage management, told me. But when a cost goes up as continuously as egg prices have, restaurants start to run out of options. Susskind noted that the Waffle House spike was not a permanent price increase but a surcharge, which leaves open the option for the chain to simply remove it in the future. The Waffle House spokesperson said in the restaurant’s statement that “we are continuously monitoring egg prices and will adjust or remove the surcharge as market conditions allow.”

All of this has hit Americans hard, because we eat quite a lot of eggs. Egg consumption peaked around the end of World War II, when Americans ate an average of more than one egg a day per person. After waning a bit in the 1990s, eggs bounced back in the 2010s: By 2019, Americans were eating an average of about 279 eggs a year—that’s five to six a week. The resurgence was due in part to the fact that, after decades of warning about the risks of high-cholesterol foods, the federal government updated its guidance. Now some Americans are cutting back temporarily, but others are attempting to stock up on several dozens of eggs at a time. In spite of all the drama of the past few years, Americans aren’t likely to go eggless anytime soon. Eggs are “so embedded in American culture,” my colleague Yasmin Tayag, who covers science and health, told me, predicting that “it will take a lot more than a few years of price shifts to change that.”

The price of eggs has become a symbol of where America is going: first as a sign of inflation, now of the ongoing bird-flu outbreak. Even if you had tuned out current events for the past couple of years—if you’d deleted social media, turned off news notifications, read only Victorian novels—a version of this news was still going to reach you, in the egg aisle of the grocery store. Stocking up on eggs or cutting back is a temporary solution to a bird-flu problem that is likely to persist. The virus, Yasmin said, will keep coming back, at least until more effective mitigation measures, such as vaccines, become widespread. And week after week at the grocery store, many Americans will feel the effects.

Related:

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- Nobody wants Gaz-a-Lago, Yair Rosenberg writes.

- How Trump lost his trade war

- Elon Musk wants what he can’t have: Wikipedia.

Today’s News

- Secretary of State Marco Rubio walked back Donald Trump’s announcement last night that the U.S. should “take over” and “own” Gaza. Rubio told reporters that Trump was offering to help clean up and “rebuild” Gaza.

- A federal judge blocked Trump’s executive order that attempted to end birthright citizenship.

- Trump signed an executive order aimed at banning transgender athletes from participating in women’s sports.

Evening Read

America’s ‘Marriage Material’ Shortage

By Derek Thompson

Adults have a way of projecting their anxieties and realities onto their children. In the case of romance, the fixation on young people masks a deeper—and, to me, far more mysterious—phenomenon: What is happening to adult relationships?

More From The Atlantic

- The dictatorship of the engineer

- Tom Nichols: Trump and Musk are destroying the basics of a healthy democracy.

- A win for MAGA’s nationalist wing

- DOGE could compromise America’s nuclear weapons.

Culture Break

Read. In All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque reinvented a genre, George Packer writes.

Try. Stop listening to music on a single speaker—you have two ears for a reason, Michael Owen writes.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.