The Political Novelist Who Never Stood Still

Mario Vargas Llosa, who died this week, traveled through both literature and politics with a heedlessness you had to admire.

“At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” So begins the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa’s 1969 masterpiece, Conversation in the Cathedral. What made the opening so famous and effective was the fact that many countries across Latin America, a landscape of shaky democracies, were asking themselves that question about their homeland. The number of people asking this seems to have grown in recent years all over the world. Perhaps you’ve asked it yourself.

Vargas Llosa, who died in Lima this past weekend at the age of 89, nurtured a lifelong obsession with his native Peru: its corrupt political ecosystem, its inequality, its incapacity to make good on its promise. He dissected that obsession in many of his 30 novels. The answers he came up with never fully satisfied him, which only meant that he posed the question from another angle in the next book. I devoured his novels before and after emigrating from Mexico to the United States in the 1980s. For many of us Latin Americans, reading him was a way to demonstrate our investment in the region’s future. His style was urbane, his research encyclopedic. His language was beautifully elastic; what fascinated me just as much was the elasticity, over decades of profound change, of his politics.

I got to know Vargas Llosa in his later years, after he had lost a run for president of Peru and won a Nobel Prize in Literature. He and I shared an agnostic attitude toward government. It is frequently said that doubt is the engine of intelligence, and he had a great deal of both. His omnivorous intellect went from one topic to another, exploring them in minute detail. Like most members of his generation—the authors of the so-called literary Latin American boom of the 1960s and ’70s, which put the region on the cultural map—he entered adulthood as a Marxist. Indeed, his education was defined by the Cuban Revolution. In a part of the world where illiteracy runs rampant, he was convinced that writers aren’t entertainers but spokespersons of the silent majority. That means that they must stand up to power.

Not surprisingly, Vargas Llosa’s early novels, inspired by the type of social realism that prevailed after the Second World War, are at their core antiauthoritarian. Because he had come of age under right-wing dictatorships, he believed that Peru’s antidemocratic spirit was rooted in the inquisitorial habits brought over by the Europeans during the conquest. Underlying Conversation in the Cathedral is a critique of the regime of Manuel A. Odría, who was the president of Peru in the 1950s.

[In the February 1984 issue: Latin America: A media stereotype]

Over time, Vargas Llosa realized that this kind of reflexive leftism was naive. The turning point came in 1971, when the prominent Cuban poet Heberto Padilla was imprisoned for speaking out against Fidel Castro’s Communist regime, which by then had aligned itself with Moscow. While other “Boomistas,” including Vargas Llosa’s pal and onetime roommate Gabriel García Márquez, looked the other way, he ferociously denounced the curtailing of free speech. (He broke off contact with García Marquez in 1976 after punching his old friend in the face on the night of a film screening.) But Vargas Llosa didn’t stop there. He also accused the Havana government of intolerance, allergy to free enterprise, and overall narrowmindedness. As a result, he quickly became a persona non grata in Latin American intellectual circles.

This was the spark that his ferociously independent spirit needed, and it deepened his literary work. His move toward the ideological center is clear in The War of the End of the World, published in 1981—my favorite Vargas Llosa book. It is about a real-life religious fanatic, Antonio Conselheiro, in Brazil’s 19th-century hinterlands, who established an autonomous republic made up of outlaws, sex workers, and beggars. The novel is a cautionary tale about populist leaders who are incapable of separating their need for adulation from the needs of their constituents. I read it almost in a single sitting when it came out. Vargas Llosa’s absolute command of the craft made clear that a key role of the novelist is to use fiction to explain the excesses of power.

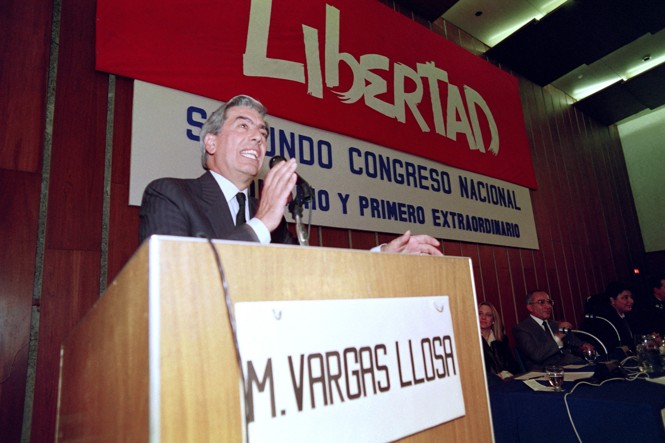

But when, in 1990, he persuaded himself that he could be Peru’s president, Vargas Llosa turned his own lessons upside down. Some critics called his campaign quixotic. There is a difference between quixotic and foolish. Throughout his run, he seemed like a fish out of water—an expression he played with for the title of the account he wrote, a few years later, about his misbegotten adventure. Not only did he lose embarrassingly, but he became a sort of avatar for Conselheiro, rallying the faithful less through reason than through charismatic fervor. He left Peru in a rush, having expeditiously secured a Spanish passport. His followers were furious. I myself thought he was a coward. We all stopped reading him. We were looking for answers to the quagmire that is Latin America, and they surely couldn’t come from a buffoon.

In Spain, however, Vargas Llosa again found a new calling. He continued meddling in politics, but more cautiously now. And he persevered in the art of the novel, although his audience was fractured (with the exception of his rapturously received 2000 novel, The Feast of the Goat, about Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, the tyrant of the Dominican Republic). His coup de grâce, and the reason I reached out to him, was the launch in 1990 of a syndicated column, “Piedra de Toque” (“Touchstone”), for the Madrid newspaper El País and its various Latin American editions. This perch allowed Vargas Llosa to comment on just about every topic he fancied, including films and fashion.

[Read: Vargas Llosa returns to his peaks]

These were only appetizers, though. Politics was always his main course. The magic wasn’t only in the style he perfected—that of a thinker digesting the contradictions of power—but in his shifting stances. In columns and speeches, he condemned the Muslim fundamentalists who conducted the Charlie Hebdo attacks and frequently assailed Vladimir Putin as a dictator. He traveled to Gaza and the West Bank, interviewing people involved with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. His views on Zionism were nuanced, denouncing extremism on both sides. He believed in a two-state solution, although he could also be disheartened about its prospects. He referred to ours as “the civilization of the spectacle.”

The ideological metamorphoses Vargas Llosa went through are not so uncommon these days: from the left to the right and vice versa, from peaceful discourse to revolutionary rhetoric, from a democratic stand to the belief in a centralized power and back. Orthodoxies no longer hold, and extremes coexist. There is, in fact, nothing unpredictable in the author’s evolution. Marxists end up ardent proponents of market economies, anti-colonialists mutate into eager interventionists, and nativists fall in love with cosmopolitanism. Most of us are more complex—and more interesting—than labels allow for. Vargas Llosa embodied those contradictions with pride, turning them into art.

I wrote to thank Vargas Llosa for his reluctance to be pigeonholed. Even when I disagreed with him—I often did—I cherished his courage to offer alternative routes of thought. We became friends, emailing on a variety of topics. I had been meaning to write again about that famous opening of Conversation in the Cathedral when I found out (from the news, like most everyone else) that he had died. I’d wanted to ask him if Peru might be seen as a synecdoche for countries all over the world—then and now. In other words, could the question at the outset of the novel be applied today to the United States—a bastion of democratic strength being ripped apart by an erratic tyrant?

Years ago, in one of his lucid columns, Vargas Llosa described the election of Donald Trump as a form of national suicide. Is Trump—I wanted to ask—like Odría, Trujillo, and Castro? In lieu of an answer, I recommend reading the novel again, now as a kind of surrogate fiction about a country in search of meaning, by a writer ready to confront our most pressing fears.