The Trump Administration Is Jeopardizing the AI Boom

A disaster for American innovation

Nearly three months into President Donald Trump’s term, the future of American AI leadership is in jeopardy. Basically any generative-AI product you have used or heard of—ChatGPT, Claude, AlphaFold, Sora—depends on academic work or was built by university-trained researchers in the industry, and frequently both. Today’s AI boom is fueled by the use of specialized computer-graphics chips to run AI models—a technique pioneered by researchers at Stanford who received funding from the Department of Defense. All of those chatbots? They rely on a training method called “reinforcement learning,” the foundations of which were developed with National Science Foundation (NSF) grants.

“I don’t think anybody would seriously claim that these [AI breakthroughs] could have been done if the research universities in the U.S. didn’t exist at the same scale,” Rayid Ghani, a machine-learning researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, told me. But Trump and the Department of Government Efficiency have frozen, canceled, or otherwise slowed billions of dollars in grants and fired hundreds of staff from the federal agencies that have funded the nation’s pioneering academic research for decades, including the National Institutes of Health and the NSF. The administration has halted or threatened to withhold billions of dollars from premier research universities that it has accused of anti-Semitism or unwanted DEI initiatives. Graduate students are being detained by immigration agents. Universities, in turn, are issuing hiring freezes, reducing offers to graduate students, and canceling research projects.

Outwardly, Trump has positioned himself as a champion of AI. During his first week in office, he signed an executive order intended to “sustain and enhance America’s dominance in AI” and proudly announced the Stargate Project, a private venture he called “the largest AI infrastructure project, by far, in history.” He has been clear that he wants to make it as easy as possible for companies to build and deploy AI models as they wish. Trump has consulted and associated himself with leaders in the tech industry, including Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and Larry Ellison, who have in turn showered the president with praise. But generative AI is not just an industry—it is a technology dependent on progressive innovations. Despite his bravado, Trump is rapidly eroding the engine of scientific innovation in America, and thus the capacity for AI to continue to advance.

In a statement, White House Assistant Press Secretary Taylor Rogers wrote that the administration’s actions are in service of building up the economy, fighting China, and combatting “divisive DEI programs” at the nation’s universities. “While Joe Biden sat back and let China make gains in the AI space, President Trump is restoring America’s global dominance by imposing tariffs on China—which has ripped us off for far too long,” Rogers wrote. (As my colleague Damon Beres wrote earlier this week, tariffs may only hurt American technology businesses.)

Despite Trump’s aims, the United States now risks losing ground to Canada, Europe, and, indeed, China in the race for AI and other technological innovation. In a Nature poll of American scientists last month, 75 percent of respondents—some 1,200 researchers—said they were considering leaving the country. New scientific and technological developments may occur elsewhere, slow down, or simply stop altogether.

Silicon Valley, despite frequently operating at odds with federal oversight, could not have come up with some of its most valuable ideas, or trained the research scientists who did, without the government’s assistance. Federally supported research and researchers, conducted and trained at American universities, helped make possible the internet, Google Search, ChatGPT, AlphaFold, and the entire AI boom (to say nothing of vaccines, electric vehicles, and weather forecasting). This fact is not lost on two of the “godfathers” of AI, Yann LeCun and Geoffrey Hinton, both of whom have lambasted the administration’s assault on science funding.

[Read: Throw Elon Musk out of the Royal Society]

“Curiosity-driven research is what allows us to explore directions that venture capital or research labs in industry would not, and should not, explore,” Alex Dimakis, a computer scientist at UC Berkeley and a co-founder of the AI start-up Bespoke Labs, told me. For example, AlphaFold—a series of AI models that predict the 3-D structure of proteins—was designed at Google but trained on an enormous collection of protein data that, for decades, has been maintained with funding from the NIH, the NSF, and other federal agencies, as well as similar government support in Europe and Japan; AlphaFold’s creators recently won a Nobel Prize. “All of these innovations, whether it’s the transformer or GPT or something else like that, were built on top of smaller little breakthroughs that happened earlier on,” Mark Riedl, a computer scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told me. Needing to show investors progress each fiscal quarter, then a source of revenue within a few years, limits what topics scientists can pursue; meanwhile, federal grants allow them to explore high-risk, long-term ideas and hypotheses that may not present obvious paths to commercialization. The largest tech companies, such as Google, can fund exploratory research but without the same breadth of subjects or tolerance for failure—and these giants are the exception, not the norm.

The AI industry has turned previous, foundational research into impressive AI breakthroughs, pushing language- and image-generating models to impressive heights. But these companies wish to stretch beyond chatbots, and their AI labs can’t run without graduate students. “In the U.S., we don’t make Ph.D.s without federal funding,” Riedl said. From 2018 to 2022, the government supported nearly $50 billion in university projects related to AI, which at the same time received roughly $14 billion in non-federal awards, according to research led by Julia Lane, a labor economist at NYU. A substantial chunk of grant money goes toward paying faculty, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers, who themselves are likely teaching undergraduates—who then work at or start private companies, bringing expertise and fresh ideas. As much as 49 percent of the cost of building advanced AI models, such as Gemini and GPT-4, goes to research staff.

“The way in which innovation has occurred as a result of federal investment is investments in people,” Lane told me. And perhaps as important as federal investment is federal immigration policy: The majority of top AI companies in the U.S. have at least one immigrant founder, and the majority of full-time graduate students in key AI-related fields are international, according to a 2023 analysis. Trump’s detainment and deportation of a number of immigrants, including students, have cast doubt on the ability—and desire—of foreign-born or -trained researchers to work in the United States.

If AI companies hope to bring their models to bear on scientific problems—say, in oncology or particle physics—or build “superintelligent” machines, they will need staff with bespoke scientific training that a private company simply cannot provide. Slashing funding from the NIH, the NSF, and elsewhere, or directly withdrawing money from universities, may lead to less innovation, fewer U.S.-trained AI researchers, and, ultimately, a less successful American industry. Meanwhile, multiple Chinese AI companies—notably DeepSeek, Alibaba, and Manus AI—are rapidly catching up, and Canada and Europe have sizable AI-research operations (and healthier government science funding) as well. They will simply race ahead, and other companies could even relocate some of their American operations elsewhere, as many financial institutions did after Brexit.

If the pool of talented AI researchers shrinks, only the true AI behemoths will be able to pay them; as the pool of federal science grants dwindles, those same firms will likely further steer research in the directions that are most profitable to them. Without open academic research, the AI oligopoly will only further cement itself.

That may not be good for consumers, nor for AI as a scientific endeavor. “Part of what has built the United States into a real juggernaut of research and innovation is the fact that people have shared research,” Alondra Nelson, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study who previously served as the acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, told me. OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google share limited research, code, or training data sets, and almost nothing about their most advanced models—making it difficult to check products against executives’ grandiose claims. More troublingly, progress in AI—and really any technology or science—depends on collaboration among people and pollination of ideas. These firms could plow ahead with the same massive, expensive, and energy-intensive models that may not be able to do what they promise. Fewer and fewer start-ups and academics will be able to challenge them or propose alternative approaches; these firms will benefit from fewer and fewer graduate students with outside perspectives and expertise to spark new breakthroughs.

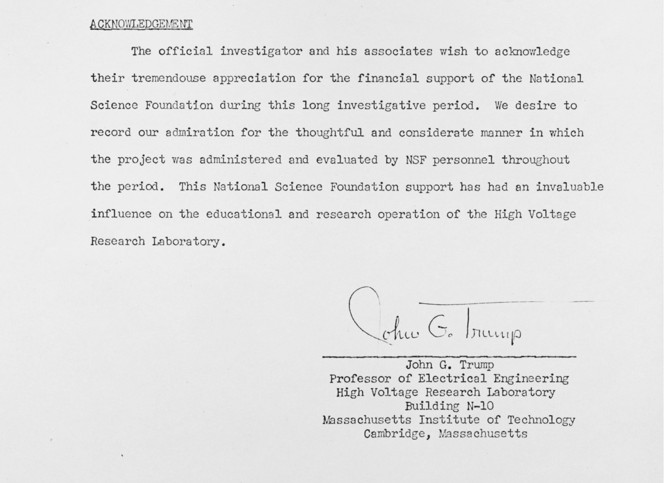

President Trump may not care much for these scientists. But there is one he holds in high esteem who might have had something to say about all this. The president’s late uncle, John G. Trump, was a physicist at MIT who did pioneering work in clinical and military uses of radiation. The president has called Uncle John a “super genius.” John Trump received a national medal of science from the NSF, and his work was supported by at least hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants from the agency—more than $4 million today—in addition to funding from the NIH, according to his papers in the MIT archives and government reports. Those NSF grants supported at least six doctoral, 20 master’s, and 13 undergraduate theses in Trump’s lab—and that was one 14-year period in the elder Trump’s decades-long career.

As I did research for this article, I found the scientist’s final research report to the NSF upon the conclusion of those 14 years, written in 1966.

John G. Trump took care to note his team’s “tremendouse [sic] appreciation for the financial support of the National Science Foundation” and its “admiration for the thoughtful and considerate manner in which the project was administered and evaluated by NSF personnel.” The foundation’s support, Trump said, had been an “invaluable influence on the educational and research operation” of his lab. Almost 60 years later, education and research no longer seem to be among the nation’s priorities.