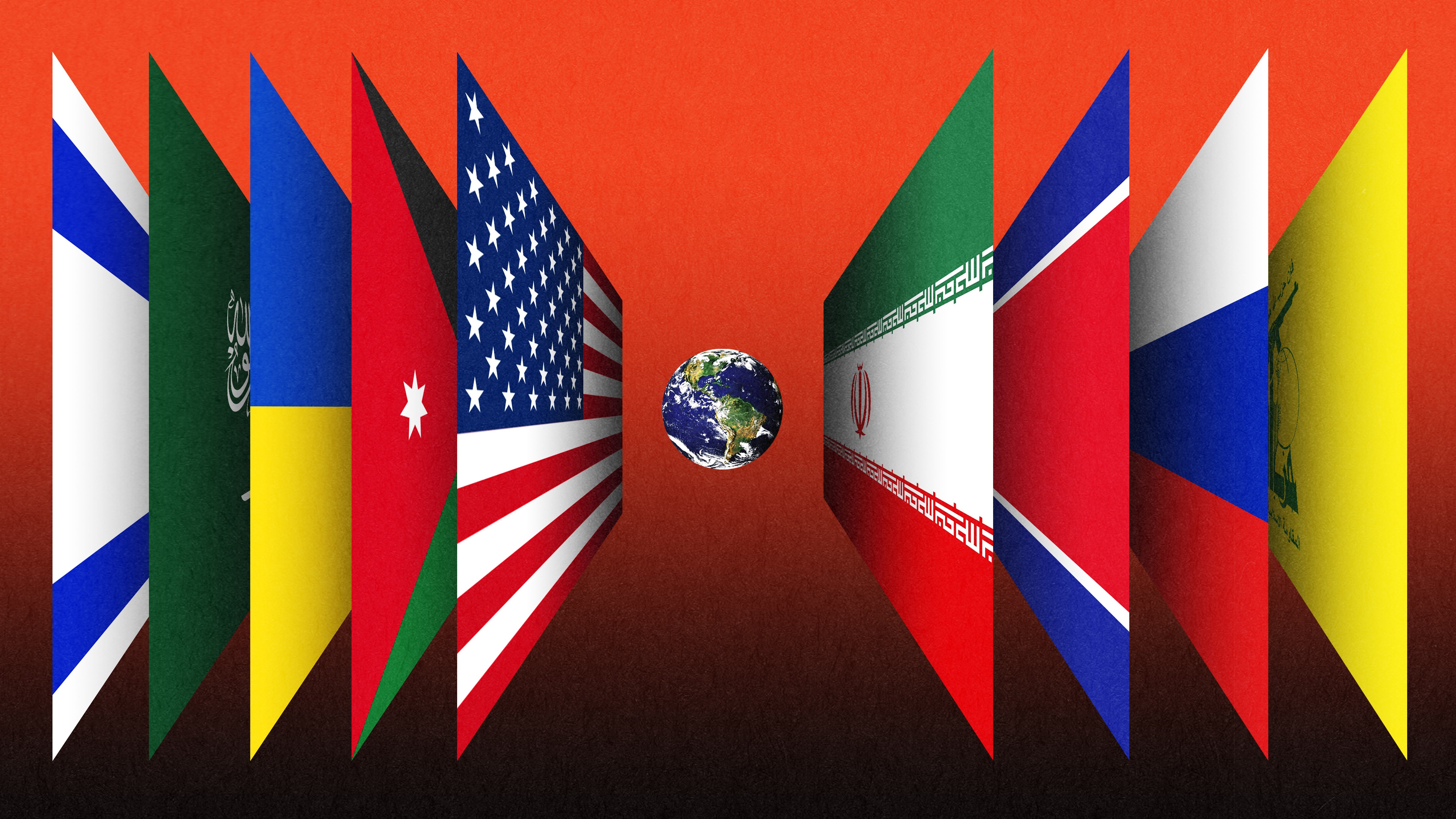

The World Is Realigning

An emerging Axis of Resistance confronts the Liberal Alliance.

Like a lightning strike illuminating a dim landscape, the twin invasions of Israel and Ukraine have brought a sudden recognition: What appeared to be, until now, disparate and disorganized challenges to the United States and its allies is actually something broader, more integrated, more aggressive, and more dangerous. Over the past several years, the world has hardened into two competing blocs. One is an alliance of liberal-minded, Western-oriented countries that includes NATO as well as U.S. allies in Asia and Oceania, with the general if inconsistent cooperation of some non-liberal countries such as Saudi Arabia and Vietnam: a Liberal Alliance, for short. The other bloc is led by the authoritarian dyad of Russia and Iran, but it extends to anti-American states such as North Korea, militias such as Hezbollah, terrorist organizations such as Hamas and Palestine Islamic Jihad, and paramilitaries such as the Wagner Group: an Axis of Resistance, as some of its members have accurately dubbed it.

With the adoption of the Abraham Accords normalizing Israel’s relationship with several Arab countries, and with the accession of Sweden and Finland into NATO, the Liberal Alliance has forged tighter ties. In response, the Axis of Resistance has adopted a more offensive posture. “This is an entente that is really coming together in a way that should alarm us quite a lot,” the American Enterprise Institute’s Frederick Kagan said recently in an interview with the journalist Bill Kristol. “These countries disagree about a lot of things; they don’t share a common ideology. But they do share a common enemy: us. And the thing that they agree on is that we are a major obstacle to their objectives and their plans, and therefore that it’s in each of their interest to help the others take us down.”

The Axis of Resistance does not have a unifying ideology, but it does have the shared goal of diminishing U.S. influence, especially in the Middle East and Eurasia, and rolling back liberal democracy. Instead of a NATO-like formal structure, it relies on loose coordination and opportunistic cooperation among its member states and its network of militias, proxies, and syndicates. Militarily, it cannot match the U.S. and NATO in a direct confrontation, so it instead seeks to exhaust and demoralize the U.S. and its allies by harrying them relentlessly, much as hyenas harry and exhaust a lion.

The Axis has thus developed into an acephalous networked actor, its member states operating semi-independently yet interdependently, taking cues from one another and sharing resources and dividing duties, jumping in and out of action as opportunities arise and circumstances dictate. One country will help another bust sanctions while receiving military equipment from a third. As The Atlantic’s Anne Applebaum has reported, Russia, Iran, and China have also joined forces on the propaganda front, launching waves of disinformation toward the West. Although the Axis normally takes care to keep its hostilities beneath the threshold that would trigger state-to-state military conflict, it can and will resort to direct military confrontation if it sees need or advantage.

In the two current conflicts, Ukraine and Israel act not only on their own behalf but also as surrogates for the broader alliance. Neither Ukraine nor Israel can sustain its position without outside support. That support, therefore, is a primary target of the Axis, which coordinates across both fronts. Russia has ditched its previously warm relationship with Israel to embrace Iran, which supplies the Kremlin with weaponry and equipment. North Korea likewise supplies the Russian war effort, and it recently entered into a security pact with Russia; Hamas praises North Korea as “part of [our] alliance.” China, while keeping some distance from the Ukraine conflict militarily, has declared “unlimited partnership” with Russia, helps Russia defeat economic sanctions, and provides industrial and technological support for Russia’s war effort. Meanwhile, Russia props up the pro-Iran regime in Syria, and militias aligned with Iran use missiles and drones to strike Israel from Gaza and Lebanon, U.S. forces from Iraq and Syria, and Saudi Arabia from Yemen. Even the weakest and poorest of the Axis forces, the Houthi rebels in Yemen, disrupt regional shipping virtually at will.

[Arash Azizi: Iran’s proxies are out of control]

The Axis’s principals make no secret of their designs. “We are fighting in Ukraine not against Ukrainians but against the unipolar world,” the Russian ideologue Alexander Dugin said at a conference in Moscow in February. “And our inevitable victory will be not only ours but a victory for all humanity … This is not a return to the old bipolar model but the beginning of a completely new world architecture.” According to the Middle East Media Research Institute, Hossein Salami, the commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, said in a speech in November, “The enemies of the Islamic regime were, and are, the enemies of all humanity, and today the world is rising up against them.” America, he predicted, will “lose [in] the political arena” and “will also fail economically … Be certain that the morning of victory is nigh.”

In the Barack Obama years, it seemed tenable to dismiss Russia as a weak and declining regional power that could slow but not block the advance of liberal democracy, and Iran as a vicious but brittle and unsustainable regime that could needle America but not challenge it. Both countries, after all, seemed beset with social, economic, and demographic problems that could hobble them in the long run. But the long run is taking its time arriving. For the moment, the Axis is playing offense and setting the tempo. Even if it cannot drive the United States completely out of Europe and the Middle East, it may well succeed in weakening NATO, dominating the Middle East, and, what is perhaps most significant, calling into question the sustainability of Western-style liberalism. As it aligns its goals and strategies across far-flung theaters, the Axis of Resistance is emerging, alongside the rise of China, as a generational challenge to the Liberal Alliance.

Americans, accustomed to gauging power by counting aircraft carriers and nuclear warheads, have until now underestimated the ambition and sophistication of the forces arrayed against us. The Axis’s strategy of harrying and exhausting us might very well work, and head-on military responses can be at best only partially effective against it. The Alliance must build a network of its own, one that can coordinate across multiple fronts to contain, deflect, and deter the Axis’s provocations. And only one of the two people running for president is capable of doing that.

In June 2021, at an annual summit in Brussels, NATO reaffirmed its commitment to the eventual membership of Ukraine, which was also in negotiations to join the European Union. Eight months later, Russian tanks were streaming toward Kyiv. NATO, the Americans and others said, could not extend its security guarantee to Ukraine during a hot war with Russia. The NATO-Ukraine deal was off, at least for the time being.

On September 22, 2023, Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, told the United Nations General Assembly that Israel and Saudi Arabia were “at the cusp” of a deal normalizing relations—a “dramatic breakthrough” and a “historic peace.” Two weeks later, Hamas, an Iran-backed terrorist organization, invaded Israel, killed 1,200 Israelis and foreigners, took at least 240 hostages, and set off a war. The Israeli-Saudi deal was off, at least for the time being.

For Russia and, likewise, for Hamas and Iran, these attacks were epic gambles, the kind of risks leaders take once in a generation. Although the gambles were made in different theaters, their cause was the same: Both actors saw time running out to stop changes they feared.

Vladimir Putin, although once more conciliatory, today describes the Liberal Alliance as Russia’s “enemy” or “adversary,” depending on the translation. He views its geopolitical goals as fundamentally incompatible with his regime’s continued authoritarian rule. In this, Putin is correct. His incorrigibly antidemocratic and corrupt government derives legitimacy from its claim of defending Russia from foreign meddling, Western humiliation, and “LGBT propaganda.” For a time, several U.S. administrations hoped to rub along with Putinism, or outlast it, or distract it with consumer goods and McDonald’s, betting that Putin and his mafia might be content to loot billions from the economy and stash the money in foreign bank accounts and mansions. But in February 2022, Putin dashed those hopes.

Why just then? Putin was not primarily concerned about NATO enlargement. NATO posed no offensive threat to Putin, and a stable and constructive working relationship was his for the asking. But Putin came to perceive any such arrangement as capitulation, and he came to see Ukraine’s independence as a historical aberration and a kind of personal insult. After the Orange Revolution turned Ukraine toward Europe in 2014, he responded by invading and seizing Crimea. That, predictably, strengthened Ukraine’s fear of Russia and its resolve to cast its lot with the West.

In 2014, when Russia’s “little green men” made fast work of Crimea, the Ukrainian state was riddled with corruption and barely democratic. But by 2022, under President Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine was tackling corruption, Westernizing, and consolidating democratic rule. Also, with the help of American military aid (the very aid that Donald Trump held up in an effort to extort political dirt from Zelensky), Ukraine was developing the capacity to defend itself. Putin could see that if he did not intervene soon, Ukraine would join the Liberal Alliance culturally through its Western ties, militarily through NATO, and economically through the European Union. Putin could foresee Russia’s sphere of influence crumbling, and with it, his own fearsome reputation. Russia feared losing a historically significant geographic buffer against invasion from the West. But much worse, Ukraine’s escape from Russia’s orbit might inspire other countries to follow. Liberal democracy, not just NATO tanks, would roll up to Russia’s border. From America’s standpoint, Putin was behaving imperialistically and militaristically. But from Putin’s standpoint, he was acting defensively against the relentless expansion of the Liberal Alliance. One way or another, Zelensky had to go.

Putin’s Russia had sometimes positioned itself as a dealmaker and even a peacemaker, cultivating relations with Israel while keeping a deniable distance from Iran—but the Ukraine invasion, and the swift and vigorous Western reaction, disambiguated the situation, firmly planting Russia in the Axis. Despite Russia’s economic and demographic decline and its stunted and sclerotic politics, its size, strength, resources, and lack of scruples transformed the Axis from a regional menace into a global one. With its successful interventions in Syria, its extraterritorial assassinations, and its aggressive propaganda and cyber operations, Russia has reached far beyond its neighborhood. Putin understands his economic and military weakness relative to the Liberal Alliance, but he is betting that he can divide the Alliance and outlast it—that he can inflict and tolerate more pain. He can look to far-right parties and leaders in America and Europe to help him. His plan is hardly fanciful. If Trump returns to office, Putin might win his bet, with America’s abandonment of its commitments to NATO.

Iran has its own plan, which also relies on harrying, dividing, exhausting, and ultimately rolling back the Alliance. Tehran has spent billions of dollars in aid, and years of military mentoring, to encircle Israel with antagonistic proxies: Hamas to the west, in Gaza; Hezbollah to the north, in Lebanon; Shiite militias to the east, in Syria and Iraq; and the Houthis to the southeast. Iran, writes Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, “is indirectly occupying four Arab capitals: Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus and Sana”—perhaps an exaggeration, but not much of one. Only along its Egyptian and Jordanian flanks does Israel enjoy any kind of security. Iran’s proxies and clients, while maintaining various degrees of nominal independence from Tehran, can harry Israel relentlessly—not just today or next year, but forever. The same proxy network can needle Saudi Arabia and America to keep them constantly jumping. “Iran has coordinated actions taken among its various proxies, including the recent attacks against U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria and the Yemen Houthis’ activities, seeking both to impose costs on the United States for supporting Israel and also to limit additional U.S. assistance,” Katherine Zimmerman of the American Enterprise Institute wrote in January. “To date, Iraq-based groups have attacked U.S. forces at least sixty-six times in Iraq and Syria since the start of this conflict, injuring over sixty troops.”

Like Russia, Iran knows that it cannot win a direct confrontation with the United States; however, also like Russia, it believes that it won’t have to. The pressure of encirclement and relentless harrying will, in its view, erode Israel’s military, divide its democracy, drive away its entrepreneurs and investors, and demoralize its population. Lacking the conditions that make a modern liberal democracy viable, Israel will collapse within 25 years, Iran’s leaders believe. Meanwhile, tied down by Iran’s unpredictable and relentless proxies and reluctant to strike directly at Tehran, the United States will become exhausted and look to exit the region, which it longs to do anyway. As Israel weakens and America withdraws, the way will be clear for Tehran’s mullahs to dominate the region, and the impotence of modern liberal democracy will be exposed.

America, Israel, and the Sunni Arab states are well aware of Iran’s strategy. Whatever the Sunni countries’ tensions with Israel and the U.S., they regard being dominated by revolutionary Iran as far worse. They have noticed that Saudi Arabia was helpless to defend itself from hundreds of drone and missile attacks by the Iranian-backed Houthis on Saudi oil facilities and cities, including a 2019 attack that knocked half the supply of the kingdom’s oil exports offline. They have noticed, too, that Saudi Arabia’s effort to flex its military muscles in neighboring Yemen was a fiasco. They accurately perceive Israel as the lesser threat, which is why Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, followed by Morocco and Sudan, took the dramatic step of normalizing their relations with Israel.

For the Liberal Alliance, though, an even greater prize seemed within reach. Threatened by Iran, Saudi Arabia wants—and needs—a formal defense commitment from the United States, beyond the informal support it enjoys already. It wants access to Israeli technology. It wants nuclear power, to hedge against a post-oil future and a nuclear-armed Iran. By October 2023, negotiations were reportedly well advanced for a deal combining those elements with formal normalization of Saudi-Israeli relations and tangible steps toward Palestinian statehood.

[Michael Schuman: China may be the Ukraine war’s big winner]

From Iran’s point of view—and, by extension, from Hamas’s—that deal would have been catastrophic. It would effectively have ended the 75-year Arab-Israeli conflict, which Iran has exploited to inflame the region and prevent an anti-Iranian consolidation. Worse still, Israeli-Saudi normalization would turn the tables on Iran’s encirclement strategy; now Iran and its allies would be the ones facing encirclement, in the form of a wall of U.S.- and Israel-aligned Arab states from North Africa to the Persian Gulf. In an interview with Thomas Friedman in January, Secretary of State Antony Blinken put the case straightforwardly: “If you take a regional approach, and if you pursue integration with security, with a Palestinian state, all of a sudden you have a region that’s come together in ways that answer the most profound questions that Israel has tried to answer for years, and what has heretofore been its single biggest concern in terms of security, Iran, is suddenly isolated along with its proxies, and will have to make decisions about what it wants its future to be.” Moreover, from Hamas’s point of view, the deal would add insult to injury by bolstering the Palestinian Authority, Hamas’s bitter rival in Palestinian politics.

And so, Iran and its client Hamas, like Putin, believed that they had to act before they found themselves walled in. They were willing to take incalculable risks, and suffer severe losses, by lighting their regions on fire.

If the clock were stopped right now, the military contest would probably be declared a draw. The wars being waged by Israel and Ukraine both appear likely to end in some form of stalemate. Israel’s military effort to eradicate Hamas will be imperfect and impermanent, and it is incurring unsustainable costs to Israel’s international reputation and relationships. Ukraine, for all its skill and pluck, lacks the manpower and resources to evict Russia from every inch of its territory. Even if American support were not already wavering, Ukraine could not indefinitely throw men and materiel at entrenched Russian positions; even if international support for the campaign against Hamas were not already eroding, Israel could not indefinitely throw its labor force into firefights in Gaza.

Militarily, in Ukraine, Putin can win by not losing. To be sure, he had hoped to topple Kyiv’s democratic government and establish a vassal state. But he can still intimidate Russia’s neighbors, divide the Liberal Alliance, and show that Western power cannot be counted on against determined Russian aggression. Even if he is temporarily stymied in Ukraine, he would be in a position to resume aggression there and elsewhere at a time of his choosing. Moreover, he can use the threat of aggression, plus relentless economic and political pressure, to strangle Ukraine’s economy and influence its politics.

The same is true for Hamas and Iran. Even though they have no hope of defeating Israel militarily, their show of force in Israel and across the region can intimidate the Arab states, divide the Liberal Alliance, and demonstrate the unreliability of Western power. By threatening aggression, keeping Israel on a permanent war footing, and destabilizing the region, they can strangle Israel’s economy and prevent Iran’s rivals from consolidating. On both fronts, the Axis can win by depriving its target countries of the conditions needed to sustain prosperity, democracy, and domestic solidarity.

Against this asymmetrical strategy, conventional military responses are of limited use. They will be necessary on occasion, but the U.S. would run itself ragged attempting to respond militarily to provocations across the Axis network, which is exactly as the Axis intends. The two current hot conflicts, in Ukraine and Israel, have already depleted American means and will.

Fortunately, whether the Axis wins its two wild gambles depends only partially on battlefield outcomes. What matters as much—indeed, more, from a U.S. point of view—is whether the U.S. and its allies can deny Russia and Iran their principal strategic aim by handing them major diplomatic setbacks. That could deter them and other powers (notably China, which is looking on and taking notes) from trying similar gambits in the future. In other words, deterrence can be established strategically as well as militarily.

In an article published in Foreign Affairs last year, just before Hamas attacked Israel, Jake Sullivan, the Biden administration’s national security adviser, touted a “self-reinforcing latticework of cooperation.” He pointed to the global coalition of countries supporting Ukraine against Russia; the expansion of NATO to include Finland and Sweden; deepened U.S.-EU cooperation; the thaw of relations between Japan and South Korea; AUKUS, a security partnership between the U.S., Australia, and Britain (an effort that Japan might informally join); the Quad cooperative framework between the U.S., Australia, India, and Japan; a new coalition with India, Israel, the U.S., and the United Arab Emirates, called I2U2; a 47-country effort to counter cybercrime and ransomware; and more.

Although talking about countering a network with a lattice sounds gimmicky, the concept is substantive and sound. The Axis is well aware that the Liberal Alliance seeks to contain its power through security agreements, sanctions, and commercial ties. The Alliance would thus establish what the Australian journalist and podcaster Josh Szeps has called “an arc of anti-Iranian and potentially anti-Chinese and anti-Russian allies stretching from South Asia through the Arab Gulf states, through North Africa, and into the European Union.” Such a grouping is far better positioned than any individual state—even if that state is as powerful as America—to outlast and outmaneuver the Axis’s strategy of harrying and exhausting the Alliance. It could operate across the Northern Hemisphere to crimp the Axis’s financial and economic resources, to blunt the Axis’s weaponization of energy and commodities, and to deflect and cushion the effects of provocations.

The most important steps that can be taken toward building out this vision are the two that Iran and Russia most fear and loathe: Saudi-Israeli normalization and Ukrainian NATO-ization. Both measures are desirable as security measures in their own right. More than that, however, they would constitute dramatic strategic defeats for the Axis. NATO membership—in tandem with European Union membership—would put Ukraine beyond Putin’s military and economic reach. Putin might wind up with a chunk of territory in eastern Ukraine, but he will have lost the subservient and illiberal satellite he sought to secure. In the Middle East, normal relations among Israel, the Saudis, and most of the region’s other Arab states, along with a U.S.-Saudi defense pact and progress toward a Palestinian state, would greatly reduce the reach, influence, and perceived success of Iran and its proxies.

Have no illusions: This is hard. Russia and Iran will try to spoil any deals by prolonging the conflicts. NATO is reluctant to provide a standard Article 5 security guarantee to Ukraine while Ukraine is in a shooting war with Russia, the Saudis are unlikely to resume negotiations on normalization while Israel is killing Palestinians, and Israel is unlikely to proceed toward a Palestinian state under its current far-right government. In both theaters, there will need to be compromises and work-arounds, as well as some stabilization of the military situations.

China also figures into the equation—albeit in a complicated way. Unlike the Axis of Resistance, China is a full-spectrum competitor of the United States, one that challenges America economically, militarily, and ideologically. But although it is adversarial, China is far more deeply integrated into, and dependent upon, the global economy than is Russia, Iran, or North Korea, and so its interests are conflicted. On the one hand, it benefits from the Axis’s strategy of keeping the Liberal Alliance off-balance and overextended, which is presumably why it sustains Russia’s war against Ukraine; on the other hand, it does not benefit from a chaotic world in which its export-dependent economy is disrupted. And so, although China’s backing increases the Axis’s resilience, China’s influence may also provide a source of restraint. For the Alliance, the trick is to separate China from the Axis and exploit their divergences.

There are domestic hurdles for the Alliance too. The U.S. Senate might balk at a defense treaty with the Saudis. Turkey and Hungary might try to block Ukraine’s entry into NATO. Although the Axis does not have many overt friends in the West, it does benefit from the support of a collection of American and European populist, isolationist, and authoritarian constituencies—MAGA World chief among them. It also benefits from anti-colonialism, anti-Zionism, anti-capitalism, and other leftist ideologies in the West that see Hamas as a liberator and the liberal project as oppressive.

Then there is the biggest potential challenge of all: Donald Trump.

Russia and Iran might well have taken their gambles no matter who was president. If Joe Biden did anything to provoke their attacks, it was the progress he made toward building a sustainable liberal coalition. Some analysts, pointing to the bungled U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, blame the Biden administration for failing to deter adventurism by Moscow and Tehran. There may be something to that charge, even though the Afghanistan withdrawal was negotiated and sealed by Trump, not Biden. A better argument, though, is that Trump’s isolationism, transactionalism, and caprice were the larger factors emboldening the Axis. It was Trump who let attacks on Saudi Arabian oil facilities go unanswered in 2019, diminishing the Saudis’ confidence in American protection and increasing the Iranians’ sense of impunity. By scrapping an agreement to freeze Iran’s nuclear program, Trump eased the way for Iran to reach the weapons threshold. By truckling to Putin in public and delaying military aid to Ukraine in private, Trump may have contributed to Putin’s overconfidence. By sowing doubt about America’s commitment to NATO, and by implying that any U.S. commitment is purely transactional, Trump undermined confidence in the Alliance.

In his 2024 campaign, Trump has gone much further than he did in the past toward repudiating America’s commitment to NATO. Although he might be able to push ahead with an Israeli-Saudi deal (his record negotiating the Abraham Accords was a bright spot), that deal will require deft handling of the Palestinian issue, in which Trump has shown no interest. Most important, however, is that Trump’s mercurial isolationism signals to the world that Americans’ will to build and maintain alliances is flagging, and it signals to the Axis that America is ready to be chased away.

Still, regardless of who sits in the Oval Office, the U.S. and the Liberal Alliance hold some strong cards. Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, and the Western-oriented counties in their regions need a new security order—and they know it. Russia’s and Hamas’s invasions have demonstrated just how vulnerable the democracies and their allies are, and how ruthless and bloody-minded their antagonists are. If Putin and Hamas did nothing else, they shattered illusions that the status quo was adequate or sustainable. No wonder the Saudis have signaled their continued desire for American protection and normal relations with Israel, that EU membership for Ukraine is on a fast track, and that NATO’s members have agreed that Ukraine will join.

[Michael Young: The axis of resistance has been gathering strength]

The latticework of cooperation, as Jake Sullivan termed it, is not notional; the world got a vivid preview in April of what it looks like. Iran and its Yemeni proxies launched more than 300 missiles and drones at Israel. All but a handful were shot down, and the remainder caused only minor damage. As significant as the interceptions was the coalition that conducted them, which included U.S., British, and French forces in the region. “Perhaps more striking,” Lawrence Haas wrote, “leading Arab nations also came to Israel’s assistance. Saudi Arabia—which, we must remember, has not yet normalized relations with the Jewish state—and the United Arab Emirates were among several Gulf states that relayed intelligence about Iran’s planned attack, while Jordan’s military reportedly shot down dozens of Iranian drones in its airspace that were headed toward Israel.” In the end, what the strike demonstrated was not Iran’s ability to attack but the Liberal Alliance’s ability to defend.

On balance, the crises in Europe and the Middle East, horrible though they have been, have improved the odds of an endgame in which Ukraine is a NATO democracy; in which the U.S., Israel, and the Arab world are linked together to contain Iran; and in which America and its allies together turn the tables on the Axis of Resistance. That strategic endgame, above and beyond any particular military outcome in Europe or the Middle East, is the victory that the U.S. should seek.