The Writer Who Understood the True Nature of Obsession

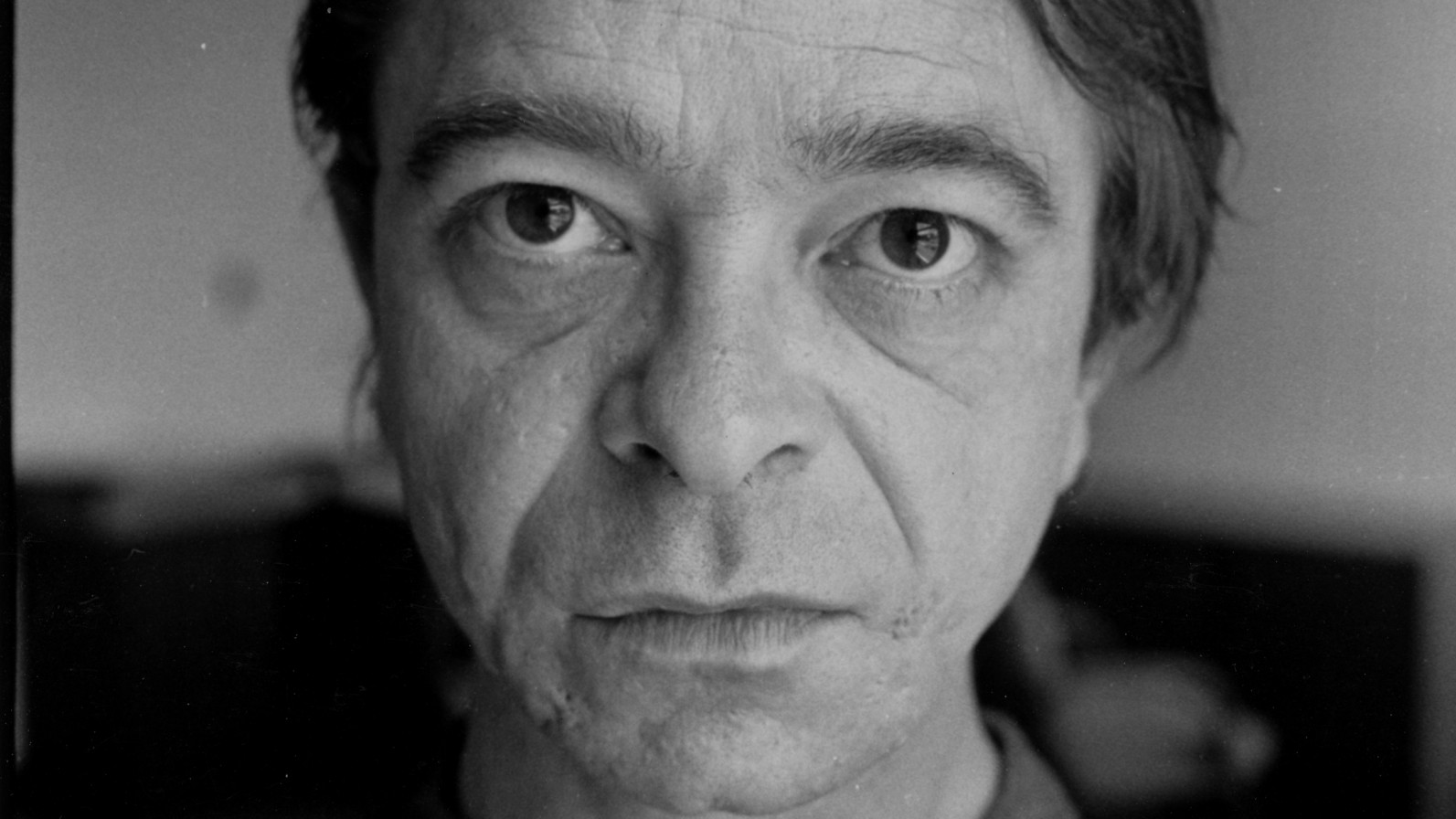

The late Gary Indiana kept the culture of his time close to his chest because it fueled his indignation—and his fixations.

The writer Gary Indiana, who died last week at the age of 74, wrote about his obsessions with the calculated grace of a man who found them slightly embarrassing. He was a stylist of remarkable erudition, and possessed a startling range; his essays, criticism, plays, films, and fiction spanned seemingly endless topics, among them French Disneyland, Cuban prisons, the journalist Renata Adler, the sculptor Richard Serra, true-crime stories, the Boston Marathon bombings, and various men whose beauty slayed him. For the past several decades, he lived in a sixth-floor East Village walk-up cramped with thousands of volumes of literature. In Horse Crazy, Indiana’s first and best novel, his unnamed narrator invites a prospective boyfriend to his similarly cluttered apartment and feels ashamed—not of its mess, exactly, but of the sheer number of books on his shelves. “I suppose this is my life,” he says, after longing “for a garbage dumpster big enough to swallow the entire past.”

Born Gary Hoisington in 1950s New Hampshire, Indiana moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the aftermath of the famed Summer of Love and spent the rest of his life unromantically hungover from the period. The bohemian artistic milieu where he came of age was shifting toward the pop, the conceptual, and the camp, but Indiana was both suspicious of the future and unwilling to be in the thrall of the traditional. He participated in the debauched, stoned zeitgeist yet wrote about sex without triumph or tenderness—his lovers were scorned, dissatisfied. After moving to New York City in 1978, he became one of the defining countercultural writers of the ’80s, a decade he skewered; his tenure as Village Voice’s art critic was notable more for what he despised than for what he liked. Yet so much of what he lampooned throughout his career obsessed him—gorgeous young gay men, bizarre drug addicts, the thorny legacy of the ’60s, the downtown Manhattan scene he all but embodied even though he refused to be affiliated with it. He kept the culture of his time close to his chest, because what was in vogue fueled his indignation.

Horse Crazy is a particularly caustic experience. The novel’s very Indiana-ish narrator has recently landed a desirable job as a cultural critic at an influential magazine—a moment of recognition that terrifies and distresses him. He has a bit of money, but he finds money disgusting; he can write about anything he wants, but this freedom feels like a prison. “The less free I am, the freer I appear to be,” he tells the reader, in one of the book’s many takedowns of the creative life. One might imagine that the 35-year-old has more tender feelings toward Gregory Burgess, a 27-year-old former heroin addict of “extravagant comeliness,” to whom the narrator writes an “old-fashioned” 20-page single-spaced letter professing his desire.

Yet Horse Crazy is one of the best American novels about obsession in part because the narrator mostly dislikes Gregory, subjecting this object of lust to the same derisive interior voice that comments on virtually every other aspect of his life. His pristine exterior notwithstanding, Gregory personifies the very elements that make the book’s protagonist want to retch: He is an ascendant photographer whose fussy, expensive prints are sourced from pornography magazines (to which he expresses a moralistic opposition that exasperates the narrator). He is extremely articulate, yet much of what he says is fatuous and clichéd, informed by undigested pop psychology picked up seemingly through the osmosis of youth. The narrator detests Gregory’s music tastes, his artistic opinions, and, after sufficient exposure, his charm. He admits to enjoying Gregory’s personality only during a shopping expedition at a Salvation Army, where the younger man picks out grotesque garments and then reveals that he chose them precisely for their hideousness—he wants to offend the sensibilities of the restaurant where he waits tables. Carried away by a rare gust of sentimentality, the enamored narrator brushes some freshly fallen snow from his beloved’s hair.

Love, in Horse Crazy, is transactional, one-sided, unconsummated, and cruel; it pushes Indiana’s fictional stand-in out of dreamy solitude and into the savage present. The insufferable facets of Gregory’s personality are reflections of Indiana’s city and era. Horse Crazy came out in 1989, at the close of a decade that saw New York wrecked by both AIDS and drug epidemics. Gregory refuses to have sex with the narrator partially because of HIV fears, even though he may be sleeping with other people. He’s duplicitous about money, and the protagonist worries that he may be supporting a drug habit. Indiana holds out the possibility that many of the narrator’s suspicions are projections of his own behavior—he, too, has a penchant for lying to his friends, borrowing cash from them, and then never paying them back. He drinks constantly and grows dependent on speed. His former lovers are dying of AIDS, and he fixates on the virus’s incubation period to figure out whether he’ll also get sick.

[Read: Street photography from ’80s and ’90s New York]

Indiana understood that romantic obsession is timeless, a perpetual coil that revolves around itself only to be severed because its ostensible focus is an individual in a particular time and place. Every detail of Gregory’s life seems dredged from a satirical version of New York City, after the so-called gay cancer was identified and before Rudy Giuliani became mayor. The restaurant where Gregory works is owned by a coke-addled Frenchman named Philippe who wields cleavers to threaten his employees—a funny and well-deployed stereotype of the epicurean figures who cropped up as Manhattan’s food scene exploded during the ’80s. Gregory’s costly photographic practice echoes the monumental Cibachrome prints of the then-buzzy artist Jeff Wall, and more generally the money that flowed into galleries throughout the decade. His apparently ham-handed embrace of identity politics (“I have no right to use images of women,” he says about his work) reflects an age when such concerns were beginning to gain prominence in art discourse. Gregory’s judgmental perspectives on sex comically echo the culture wars raging in the United States when Horse Crazy was published. If the novel’s narrator, and perhaps Indiana himself, found these things alternately tiresome and foreboding, they also drew him out of his life and his walls of books, offering the vague promise that he could be a lover and not an observer—which is to say, that he could be less like himself.

But Horse Crazy, like much of Indiana’s output, avoids a thoroughgoing cynicism even as it disregards affection as “the mortal illness of lonely people.” Indiana diminished concepts such as love and hope not because his life or his work lacked them, but because he didn’t want these nebulous formulations to be used as Band-Aids on chronic societal problems and symptoms of the human condition. In Horse Crazy, his implacable skepticism forces the reader to consider the alienating effects of an era characterized by lethal STIs, unrepentant capitalism, bulldozed cultural history, and pervasive substance addiction. The book’s true love affair is with what cannot be reclaimed: a world untouched by disease and unspoiled by money. Indiana’s idea of being truthful was to react exactly the way his epoch needed him to. The withering vestiges of avant-garde New York—the writers, critics, artists, filmmakers, and dancers who have hung on since its peak—feel a little less vital today without his contempt.