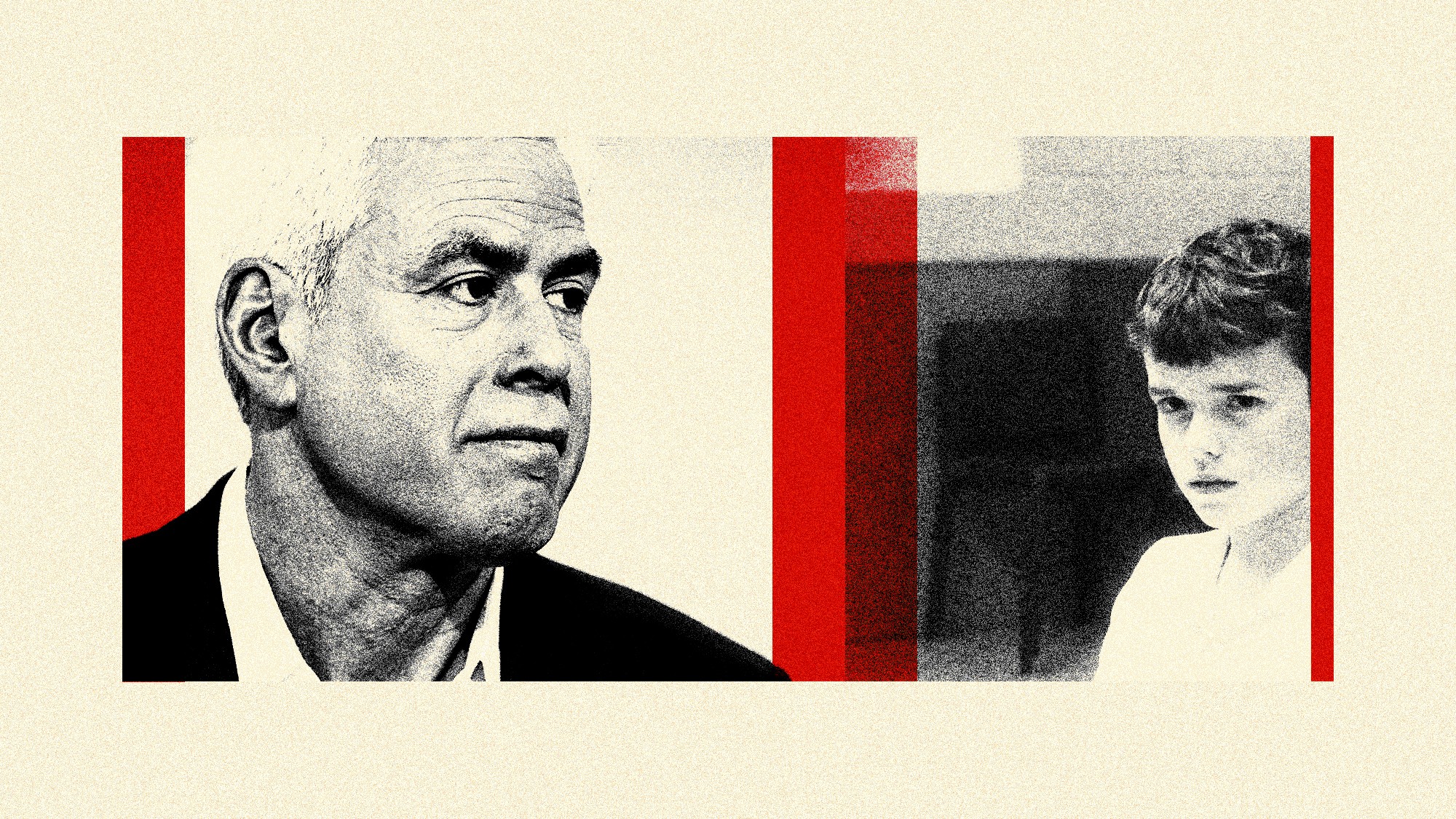

What Jonathan Haidt Thought When He Watched <em>Adolescence</em>

“The internet is just not a good place to let your child roam free 24/7.”

Adolescence, the Netflix miniseries, presents a terrible possibility—that a seemingly “good” kid in a normal English town, with two well-meaning parents, could be drawn so far down the poisoned well of the internet that he stabs a classmate to death.

Terrible, but not unfathomable: Just last year, a 17-year-old in England stabbed several children to death after viewing violent instruction manuals online. Social media is also rife with cruelty and harassment that has led to other tragedies: In 2023, a 14-year-old in the United States died by suicide after being bullied over a TikTok video, an incident that echoed several others.

Phones and screens play an important role in the show. At home, Jaime, the 13-year-old accused killer, has a computer in his room, which his middle-class father was proud to be able to give him. At school, teachers entreat students to put their phones away, mostly unsuccessfully. The teens bully one another online through emoji-dotted Instagram comments—a code that the adults in their lives struggle to crack.

[Jonathan Haidt: End the phone-based childhood now]

The show raises questions for parents about how to monitor, or restrict, their kids’ use of devices and social media. (The first and fourth episodes, in which Jamie’s father weeps over his own failures, made me want to phone-proof my kid until college.) For answers, I reached out to Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at NYU and the author of The Anxious Generation. For years, Haidt has been begging parents and schools to prohibit smartphones until high school and to keep kids off social media until the age of 16. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Olga Khazan: What was it like for you to watch this show and see it explore so many issues that you focus on in your work?

Jonathan Haidt: The main reaction that I had was as a father. In many ways the father is the essential character, and those iconic, painful scenes at the end of the first and fourth episodes really hit me. Another thing was that, while I was expecting it to really focus on social media, I really appreciated the fact that it was more about the complexities and difficulties of adolescent life and family life, many of which are made more difficult by social media. It portrayed a view of adolescence that was fairly bleak, not much fun, not much learning. And while it didn’t blame that all on social media, there were hints that the phone-based and screen-based childhood was making friendship and learning more difficult.

Khazan: What do you make of the show’s premise that a 13-year-old would kill his classmate over Instagram comments that she made about him?

Haidt: Killings are thankfully rare in the U.K. But what I was more focused on was the theme that I’ve seen since I began doing this work, in the late 2010s, which is that we all thought our kids were safe as long as they were in their bedrooms on a computer. The smartphone has made it possible for literally half of our children to be online almost constantly. The dose makes the poison, so a little bit of online life sitting at your parents’ computer in the ’90s was fine, but living your entire life on a hyperactive commercial platform whose business model is to maximize engagement is not fine. That was one of the key ideas—that the son was just up in his room on his computer all the time, and his parents were uncomfortable about it, but they didn’t think it was anything they had to intervene in.

Khazan: The school seemed to have a no-phones-in-class policy, which is something that schools in the real world are also considering. Is a policy like that sufficient for either stopping online bullying or reducing some of these other harms that you’re talking about?

Haidt: Well, first, the school did not have a no-phones policy. They had a rule that you’re supposed to keep your phone in your pocket. But that’s not a phone-free school, because teenagers cannot help it, so many are addicted. And so schools that say “We banned phone use in class” but leave the phone in the pocket, they have constant conflicts and struggles, and we saw that in Adolescence. I think it’s an argument for truly phone-free schools, which are becoming more popular. It’s only if you separate the kid from the phone, put it in a pouch or a locker, and they get it back at the end of the day—that’s going to slow down some of the warp-speed bullying, rumor-mongering, and drama.

Khazan: On the show, the kids are really mean to one another. Even in school when they're not on their phones, they’re mean interpersonally. What would you say to people who would argue that kids will find a way to bully one another even without social media?

Haidt: Once again, it’s a question of quantity. Of course they will still bully. But if you have something that is greatly ramping up the ease and availability of bullying, that’s going to really change childhood. It used to be that kids couldn’t be bullied on the weekends, they couldn’t be bullied in the middle of the night. But now it’s 24/7, and I think this is why there is a close connection between cyberbullying and suicide. There will be meanness and cruelty, but your childhood is very different when that’s just a feature that pops up here and there, versus when everybody is watching such things happen every day. It’s a question of proportion.

[Read: It sure looks like smartphones are making students dumber]

Khazan: We’ve heard a lot about the effect of Instagram on teen girls, but I thought what was interesting about this show is that it focused on a teen boy. I was wondering if we know anything about the impact of Instagram or other social media on boys, specifically.

Haidt: When I started writing The Anxious Generation, I thought it was going to be a story about girls and social media, because that's where we have the most data. But by the time I finished the book, I realized that the boy story is very different. It’s much more about addiction, violence, drug use, and radicalization.

Khazan: One thing I’ve heard from parents is that the schools are giving kids a laptop or tablet and expecting them to do homework on it, and then it becomes hard for parents to monitor what the kid is doing after the homework is done. What should parents do if their child’s schoolwork actually involves a lot of computer use?

Haidt: They should scream like hell. Whenever a kid is on a multifunction device, they will do multiple things. Laptops and tablets are major distraction machines. They are one of the reasons educational performance is going down. As soon as we started putting a computer or tablet on every kid’s desk, that’s exactly when the educational decline began. The evidence to date seems to suggest that these devices are doing more harm than good.

Khazan: Okay, so you would recommend that parents actually talk with the principal, or whoever’s in charge, and say, “Can we rethink this policy?”

Haidt: Yes, that’s right.

Khazan: Here’s one for the parents of teens. What are you supposed to do if your kids get really, really mad at you for not letting them have an Instagram account, because everyone else has an Instagram account?

Haidt: I know that situation because that’s the policy that I had with my kids. And the first thing is that it is true that they are missing out if they’re not on social media, but in the long run, they’re missing out on a lot more if they are on social media. So in the big picture, it is still very important to delay, and I urge a norm of delaying until 16.

Until now, many of us have been in a situation where our child could honestly say, “I’m the only one who doesn’t have it,” but that was in the past. Things are changing very fast already. Many parents are now delaying. So from here on in, it’s unlikely to be the case that any child is the only one who does not have a social-media account. This is a collective-action problem, and until now, all of us were stuck with the pressure to give in, because everyone else gave in. But going forward, there are enough of us that the best a child can say is “Mom, some of my friends have social media and I don’t.”

Khazan: How do you balance giving your kid more independence with monitoring what they do online?

Haidt: The internet is just not a good place to let your child roam free 24/7, especially at night and especially after bedtime. If you live in a house where out the back of the house is a wild jungle full of predators, and out in the front of the house is a meadow with bunny rabbits, and you let your kids roam in the back, but you don’t let them out in the front, you’re misallocating your protective instincts, right? To say we have overprotected our children in the real world and under-protected them online is no contradiction. It’s a statement of the realities.

[Read: The teen-disengagement crisis]

Khazan: You’ve written that phones are “experience blockers,” meaning they keep kids from experiencing the real world, and I totally see how that can be. But there are a lot of kids who are not old enough to drive, and whose parents don’t or can’t drive them places, and who, if they weren’t on their phone, would just be kind of lonely. Are you sure there are no redeeming elements to being able to connect with your friends from your home, to FaceTime with your friends, maybe even Instagram chat?

Haidt: Sure, but the claims made for the benefits of social media are almost invariably benefits of the internet, not social media. The internet made it possible for people to meet other people and to talk for free. But when social life became dominated by three or four giant platforms that used algorithms to funnel content to people, all under an advertising-based business model that prioritizes engagement, this is not connection; this is manipulation and addiction. The internet helps people connect, telephones help people connect, FaceTime helps people connect, but swiping through an infinite feed does not.

Khazan: Just to clarify, you would say that a kid should be allowed to FaceTime their friends from home?

Haidt: Yes, absolutely. Of course, that’s a good thing. Direct one-to-one communication is great. It’s very important to separate the internet from social media. One-to-one synchronous interaction is great. What’s not healthy is any sort of one-to-many performance, especially when it’s asynchronous, because that’s where the girls in particular get sucked into perfectionism and careful editing and carefully thinking through every word. It’s posting that seems to especially have a bad effect on teen girls.

Khazan: What do you see as the value of a show like Adolescence in terms of raising awareness or starting a conversation? In your experience, do people actually change their behavior after seeing a show like this, or do they just watch it for entertainment?

Haidt: When a work of fiction has an effect on a society, it’s usually not going to be just because the work of fiction was so persuasive that it changed everyone's minds. You have to look at where the audience was. And if the audience was already feeling that something was wrong, something was weird—and then a dramatic production puts it into a drama that we can all watch and talk about—then you can get a very rapid transformation of what psychologists call the common knowledge. We may each have been feeling that there was something wrong when my kid is spending every night or every weekend glued to her phone, swiping. But only once we realize that everyone else shares these concerns can you get very rapid change.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.