What to Read When You Have a Crush

The entire experience of love, these books argue, is a story in need of telling.

When does a crush begin to feel like love? This is hard to answer. How can we define that emotion well enough to demarcate its beginnings and endings? We’re familiar with the rush of infatuation, and we can recognize alienation and heartbreak, but what distinguishes the moments in the middle? Writers have long obsessed over these questions, working to capture and understand love, romance, and their effects.

In 1997, for example, Vivian Gornick wrote that love was no longer the primary narrative conflict of contemporary literature. Her provocative argument—that cynicism, sadness, and cultural fatigue have eroded our faith in the transformative abilities of romance—is one I keep returning to. It’s true that many readers know for themselves, or will discover, that passion sometimes does fail to live up to such high expectations. Much contemporary writing exhibits despondency about the possibilities of relationships. But I don’t necessarily agree with Gornick: Many other books still challenge or complicate what we believe about devotion, courtship, or even an acute crush. The books below are all, in their own way, exquisite arguments for the enduring necessity of the love story. Even when they describe bitterness or loss, they convince us that we’re capable of our own grand romance—or at least that we shouldn’t give up entirely on the whole mess.

The End of the Novel of Love, by Vivian Gornick

“Strictly speaking,” Gornick writes of the author Grace Paley in this collection, “women and men in Paley stories do not fall in love with each other, they fall in love with the desire to feel alive.” This book is a compilation of Gornick’s critiques of writers such as Willa Cather, Kate Chopin, Raymond Carver, and Jean Rhys; in every one, Gornick presents a psychologically precise rendering of their characters, making them fully human. The fiction of her time, she explains, lacks the sense of risk faced by classic protagonists such as Emma Bovary and Ellen Olenska, who really did have everything to lose for love. My favorite section is her meditation on Hannah Arendt’s flame for Martin Heidegger, which seemingly led Arendt to betray her own political and intellectual values. This is truly where Gornick shows why love deserves more recognition. “What it comes down to is this,” she writes. “If you don’t understand your feelings, you’re pulled around by them all your life. If you understand but are unable to integrate them, you’re destined for years of pain. If you deny and despise their power, you are lost.”

I Can Give You Anything but Love, by Gary Indiana

I first read Indiana’s 2015 memoir when I was assigned to write about an odd film—part performance-art piece, part proto-reality-television show—called The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd. The only person I recognized on-screen was Indiana, and his brief scenes as one of Ferd’s lovers contained what I already adored about his writing—the wry approach to melodrama; the cutting sincerity. I soon discovered that Ferd Eggan is something of a main character in Indiana’s own life story. Eggan, who died in 2007, was an activist who had a pivotal relationship with Indiana; their early sexual affair became a lifelong friendship. In Love, Ferd is always there: The underlying tensions of their attachment are still unrealized; they’re responsible for each other’s happiness, but struggle to meet each other’s needs. Indiana writes beautifully about idealizing, then recognizing, Eggan, a person who held onto his heart for a long time. Indiana’s prose adds up to a completely unsentimental yet totally romantic approach to sex, affection, and the maddening prospect of being deprived of all of the above.

[Read: The only two choices I’ve ever made]

Rapture, by Susan Minot

Perhaps some people are drawn to the thrill of an affair more than they are to a relationship itself. Benjamin, the engaged, philandering filmmaker in Rapture, may be that kind of person. The single, commitment-averse production designer Kay, despite her best intentions, most likely is as well. The book takes place over the course of one afternoon blow job, while both participants remember the entirety of their entanglement. They met on the set of Benjamin’s movie, a workplace well suited to the intensity and brevity of an affair. Kay believes that there is no chance she will fall in love, but when Benjamin says he knew his life would be different the second he saw her, her longing takes over. Technically, their fling has ended before the book begins, and yet here they are, somewhat in awe of the mysterious conspiracies that must have occurred to get them back into bed together. In Kay’s moment of complete focus on Benjamin’s body, Minot writes, “the intensity of her conviction was so strong she felt it must be making her body glow, like something radioactive.” Toxic is too soft a word: This is a tale of indulgent self-destruction as much as it is a testament to the undeniable power of sex, during the act and in memory.

See Now Then, by Jamaica Kincaid

Kincaid’s novel introduces readers to Mr. and Mrs. Sweet and their two children, Heracles (like the son of Zeus and his human mistress) and Persephone (like the queen of the dead, a symbol of the cycles of renewal that happen below the earth). Approaching time much the way Virginia Woolf did, Kincaid dispenses with linearity, crisscrossing among the beginning, middle, and end of the suffocating Sweet marriage, which is losing love by the minute. Greek tragedy is laid over pop culture: Mrs. Sweet and the kids get Happy Meals and watch the 1997 NBA finals; she says “This is just like Homer” so many times and with such gravitas that her son uses the phrase to mock her, but the comparison remains. When See Now Then was first published, some critics seemed preoccupied with how much of the novel is fiction and how much is based on Kincaid’s real marriage to Allen Shawn. But more interesting is how Kincaid precisely depicts the feeling of living with the vitriol of a man who has not yet given himself permission to leave you.

Sula, by Toni Morrison

In the introduction to the 2004 edition of Sula, Morrison shares the queries that drew her to write a novel about a lifetime of companionship: “What is friendship between women when unmediated by men?” she asked herself. “What choices are available to black women outside their own society’s approval?” The story of Nel, a shy girl subdued into submission, and Sula, made reckless by her need to experience the world, is about how they needed each other. Together as “solitary little girls,” Morrison writes, they can believe they are practically the same person. But this oneness is too much for them as adult women, and the priority of marriage is a threat to their friendship. Sula leaves the place where they grew up, while Nel stays; when Sula returns, she sleeps with Nel’s husband. They spend the following decades inside the pain of this rupture. Morrison does so much in the scenes of separation between the pair, showing how their distance is just as powerful a force as their closeness was, all leading up to the heartbreaking final paragraphs as Nel realizes what they both lost when they lost each other.

[Read: What if friendship, not marriage, was at the center of life?]

A Year on Earth With Mr. Hell, by Young Kim

This is a memoir about an affair, Kim tells us from the very first pages. It begins during a date with Richard Hell, the formidable writer, critic, and member of New York’s 1970s punk scene. Kim and Hell discuss his girlfriend. This doesn’t bother Kim so much, or maybe at all. More interesting are the many ways that Hell is like her. She explains that even though muses are traditionally cast as women, Hell was hers: a source of inspiration and energy in how she lived, moved, dressed, touched, and, finally, wrote. Their entanglement is the first she embarked on without assuming it would translate to a longer commitment. “I was intrigued and just wanted to enjoy myself,” she reflects. And there is such excitement, texture, and true pleasure in this book—in, say, Kim’s descriptions of her wardrobe, and her intimate understanding of how and why she must wear certain outfits for a certain moment. Like the Ian Fleming quote that acts as one of the book’s epigraphs suggests, Kim seems captivated by the “finest, cleanest” form of love: lust.

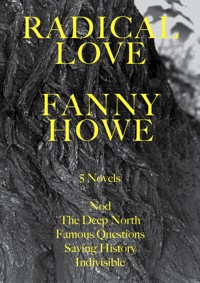

Famous Questions, by Fanny Howe

The collection Radical Love includes five novels by Howe, all of which deal with different interpretations of devotion or, as Howe puts it in the introduction to the 2006 edition, “religious experience.” Inside is Famous Questions, which is about love as a destructive, spiritual force—about how it splits people apart in the name of bringing people together. It begins with Roisin and Kosta, partners who are raising Roisin’s son, Liam, and living with Kosta’s mother. They impulsively pick up a young, pretty hitchhiker who tells them her name is Echo. This leads to a sharp and humid love triangle, in which Roisin must deal with her own warmth toward Echo while watching Kosta fall for her, until the plot crests through a breathtaking act of betrayal. The questions Howe asks are classic for good reason: Can anyone ever let anyone else in, really? And once they have, can they let go? The last lines provide a kind of answer that might take someone a lifetime to understand and express—that the only reassurance two people can give each other is that they share a story, and to agree on what that story means.