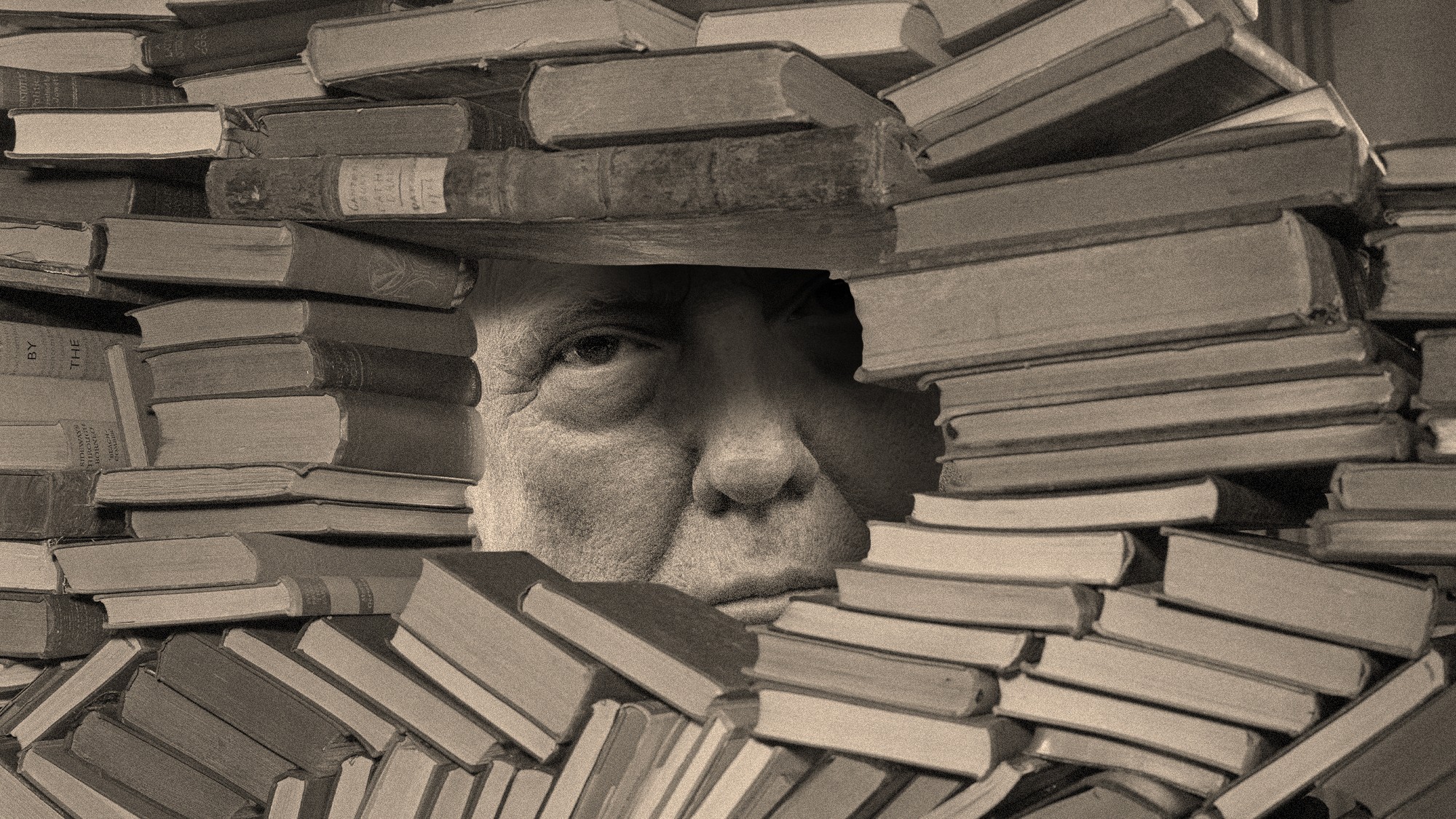

What’s Next for America’s Largest Creative-Writing Conference

Trump’s executive orders have made it downstream to authors.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Last week in Los Angeles, the author Roxane Gay gave the keynote address at the AWP Conference & Bookfair, the U.S.’s largest annual gathering of creative writers. Much of Gay’s speech focused on what she called “the abhorrent path that this country is on,” but the evening began with a tentative note of optimism: A board member for the Association of Writers & Writing Programs announced that the fair had registered 10,000 guests for the first time since the coronavirus pandemic began. As she exhorted the audience to celebrate, one woman behind me said, “Before they make it illegal.”

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s books section:

- The best American poetry of the 21st century (so far)

- What to make of miracles

- Why we’re still talking about the “trauma plot”

- Who needs intimacy?

The friendly heckler was not being entirely hyperbolic. This group of professors, students, and MFA-program directors have plenty of reason to worry: According to its mission statement, AWP takes pride in “championing diversity and excellence in creative writing.” The conference’s panels feature land acknowledgments and names such as “Queering Form” and “Postcolonial Prosodies.” You’ll find no evidence here of a “post-woke” era.

Yet AWP also serves a constituency of university-affiliated writers who depend on a substantial amount of funding from government agencies such as the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA)—whether through individual grants or via the federal money that goes to their institutions. Receiving that cash is now conditional on compliance with the Trump administration’s flurry of executive orders forbidding the mention of DEI. Just a week before the conference, Columbia University, which hosts a well-known writing program and was at risk of losing $400 million, capitulated to government demands that it curtail campus protests and place an entire department under receivership. And across the MFA landscape, academics are facing stark choices between free speech and government support as many universities purge references to race, gender, and disability from their websites and public materials.

To observe the chilling effect, all you had to do was walk the expansive floor of the West Exhibit Hall of the Los Angeles Convention Center, where program directors were hawking literary journals and MFA brochures. At the spacious University of Iowa booth, Loren Glass, the chair of the university’s English department, told me that conferences are drawing more scrutiny this year. “We’ve all been encouraged to render generic our travel plans—let me put it that way,” he said. “Like, if you’re going to a queer-studies or African American–history conference, try and call it just the AHA or the Literature Association.” A couple of aisles over, Heather Scott Partington, the president of the National Book Critics Circle, had lost her voice after pulling triple duty at her booth; Partington said two of the NBCC’s board members had canceled plans to attend the convention after their universities advised against expenditures that a government audit might later deem wasteful. (AWP’s executive director, Michelle Aielli, confirmed to me that a number of members had canceled plans to attend.)

Glass was at the fair with Christopher Merrill, the head of Iowa’s prestigious International Writing Program, which had just lost nearly $1 million in funding—or roughly half of its budget. Launched in 1967 with help from the State Department, the program has hosted authors from abroad, including the Nobel laureates Orhan Pamuk and Han Kang, and advanced American soft power. Merrill spoke with me at the fair about a new aspect of his job: frantically asking donors to close the gap. “I have to let about half my staff go, and we have to figure out an alternate means of revenue,” Merrill said, calling his curtailed program “just one of the many canaries in the coal mine.” When I asked who else in the hall might be in a similar position, Merrill said, “Actually, every one of us is a canary now.”

With universities, law firms, and corporations already backing down from Donald Trump’s challenges, Aielli, reached by phone after the fair, insisted that AWP will not do the same. “As of right now, the plan is not to scrub our website, not to change words, and, more importantly, not to change our mission,” she told me. Anticipating the loss of a sizable NEA grant, she is working to hire a development specialist: “Our goal is to try to focus on other areas of fundraising.” If AWP loses the government money, can the organization and its conference survive at their current level? “I feel confident that we can,” she said. “Can I say with certainty? I cannot, not at this time.” She expects to hear more from the NEA next month.

What to Read

Ripley’s Game, by Patricia Highsmith

The suave serial murderer Tom Ripley’s actions can be notoriously hard for readers to predict—but in Highsmith’s third novel about the con man, Ripley surprises himself. No longer the youthful compulsive killer of The Talented Mr. Ripley, the character is aging and getting bored. So when a poor man named Jonathan responds coolly to him at a party, Ripley fashions an elaborate drama for his own amusement: He cons the mild-mannered and entirely inexperienced Jonathan into taking a job as a freelance assassin targeting Mafia members, but the more Ripley watches Jonathan struggle with the task and his morals, the more Ripley itches to get his own hands dirty again. When I revisited Highsmith’s books ahead of their (rather dour) Netflix adaptation, I found myself unexpectedly drawn most to Ripley’s Game and its absurd humor. The novel explores a classic Highsmith preoccupation: how reducing strangers to archetypes can feel irresistible. Ripley is as much a petty meddler as he is a cold-blooded murderer—and that makes him endlessly fun to follow. — Shirley Li

From our list: The 2024 summer reading guide

Out Next Week

???? The Once and Future World Order: Why Global Civilization Will Survive the Decline of the West, by Amitav Acharya

???? Authority, by Andrea Long Chu

???? Audition, by Katie Kitamura

Your Weekend Read

Quaker Parents Were Ahead of Their Time

By Gail Cornwall

It can be scary to trust children with independence. But kids are better problem-solvers than some people might think. When my son, at age 10, asked me if he could play laser tag with friends, I asked him how he could avoid pulling a trigger (in deference to the Quaker value of pacifism). He decided to serve as referee. I was proud of him for exercising “discernment,” another Quaker value, all on his own, for listening to his “still, small voice within” and letting it guide him to a solution that satisfied his need for belonging. He is now 13 and recently couldn’t decide whether to accept a babysitting job or relax at home. I asked him, “What do you think tomorrow-you will wish today-you had done?” He picked out stuffed animals to give his charges, spent the evening feeling needed, and had cash the next day when he wanted to buy boba for a friend.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.