Who Are We, Really?

A new subgenre of literature explores what's uncovered when you take away someone's public-facing persona.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

If someone had no relationships—no colleagues to appease, no parents to make proud, no lovers to impress—how might they behave? With those interactions removed, would you be able to glimpse, as Jordan Kisner wrote in our May issue, an “authentic, independent self”? The author Katie Kitamura, whose new novel, Audition, is the subject of Kisner’s essay, isn’t sure. As she said in a recent interview, “When you take away all of the role-playing, all of the performance, what is left?” It could be someone free and real, or it could be “a profoundly raw, destabilized, possibly non-functioning self.” Audition, as Kisner notes, is part of a recent subgenre of literature that explores this very question. The book is the last installment of a loose, thematically connected trilogy from Kitamura; it follows a nameless actor who reveals very little of herself, instead conveying the words, identities, and stories of the characters she plays.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- The comic-book artist who mastered space and time

- The new king of tech

- A love-hate letter to technology

Though we don’t know much about the main character, her gender is crucial to the story: Women, Kisner argues, are frequently defined by their roles, as mothers, say, or wives, before being appreciated as individuals. Kisner identifies a number of books that imagine a woman who is “extracted from her core relational ties.” Protagonists in, for example, Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation seem somewhat vacant and alienated from the people around them. In many instances, readers don’t know their names or the basics of their backstories. Even the characters themselves, Kisner observes, seem unsure of who they really are.

Audition fits firmly in this new tradition. At some point, its protagonist realizes that despite their domestic routines, she and her family have been doing nothing more than “playing parts.” This moment, Kisner writes, is a key turning point that dispels “any illusion that intimacy is possible”: If there’s no such thing as an authentic self, then how can a connection between two people be anything more than an act?

Even if our identities are defined by our relationships, and even if those relationships can feel rote or false, I feel more convinced than Kitamura that we each have a unique, singular core. Accessing it might, however, require carving out time for certain pursuits that are ours and ours alone: perhaps experiencing or creating art, seeing new places or wandering around one’s own city, dedicating oneself to work or even to a quiet moment of reflection. And although the books Kisner considers tend to eschew this inner self, other recent fiction demonstrates how to access and nurture it. Rosalind Brown’s novel, Practice, which came out last year, is in some ways the opposite of the books Kisner writes about: The character at the center is rendered not in relation to others but on her own, as a student at work (in her case, an essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets). Where Kitamura uses her protagonist’s vocation as a means of stripping away her sense of self, Brown does the opposite. Her narrator luxuriates in her labor, and as we watch her ruminate, muse, and savor the writing of others, we learn a lot about who she is too.

Who Needs Intimacy?

By Jordan Kisner

Influential novelists are imagining what women’s lives might look like without the demands of partners and children.

What to Read

Famous Questions, by Fanny Howe

The collection Radical Love includes five novels by Howe, all of which deal with different interpretations of devotion or, as Howe puts it in the introduction to the 2006 edition, “religious experience.” Inside is Famous Questions, which is about love as a destructive, spiritual force—about how it splits people apart in the name of bringing people together. It begins with Roisin and Kosta, partners who are raising Roisin’s son, Liam, and living with Kosta’s mother. They impulsively pick up a young, pretty hitchhiker who tells them her name is Echo. This leads to a sharp and humid love triangle, in which Roisin must deal with her own warmth toward Echo while watching Kosta fall for her, until the plot crests through a breathtaking act of betrayal. The questions Howe asks are classic for good reason: Can anyone ever let anyone else in, really? And once they have, can they let go? The last lines provide a kind of answer that might take someone a lifetime to understand and express—that the only reassurance two people can give each other is that they share a story, and to agree on what that story means. — Haley Mlotek

From our list: Seven books that capture how love really feels

Out Next Week

???? Fugitive Tilts, by Ishion Hutchinson

???? Vanishing World, by Sayaka Murata

???? Lost at Sea, by Joe Kloc

Your Weekend Read

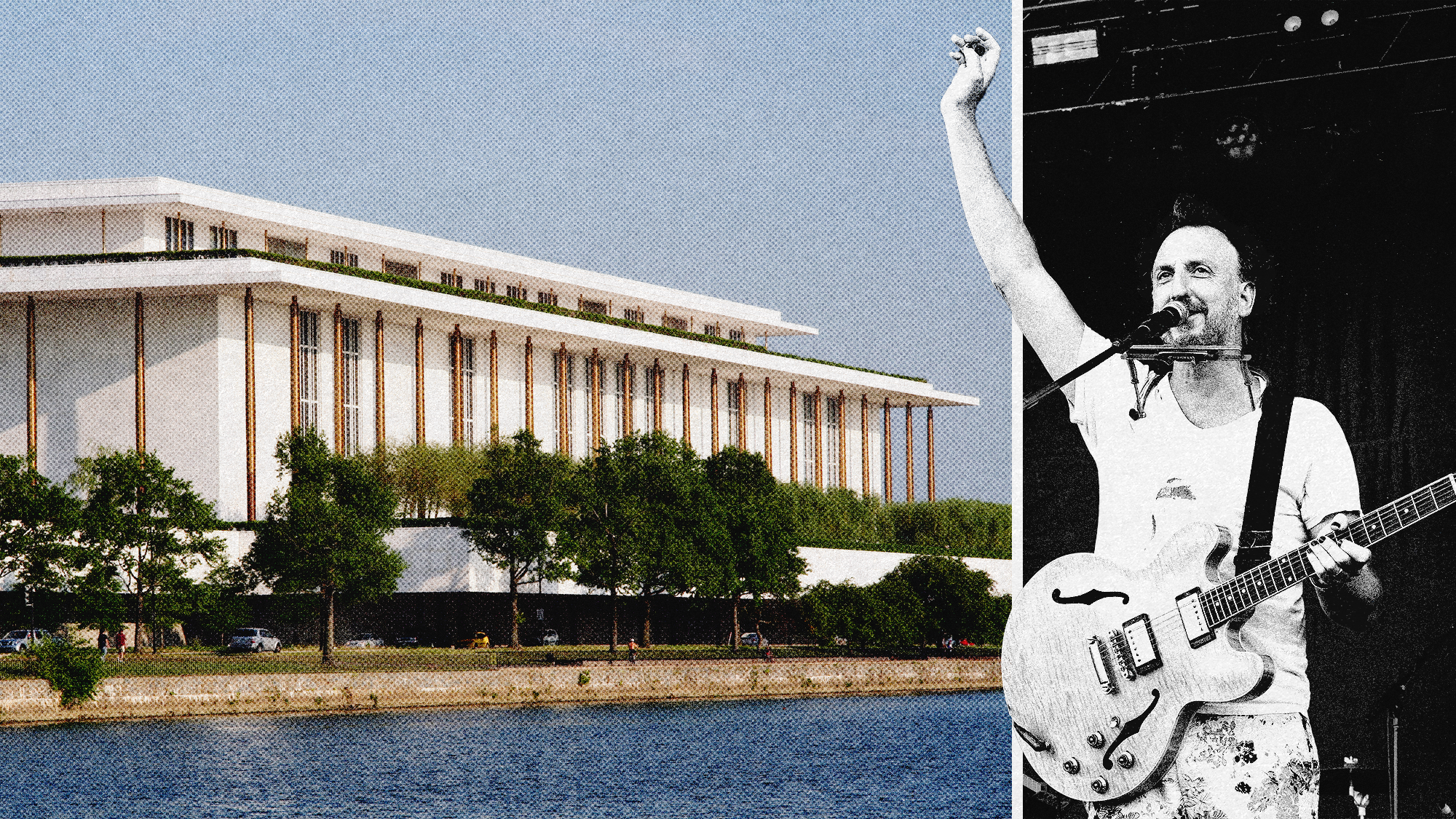

Why I Played the Kennedy Center

By Ryan Miller

As our Kennedy Center dates approached, the headlines stayed tumultuous. The juggernaut musical Hamilton announced that it was canceling its 2026 run at the venue. Others remained steadfast. Conan O’Brien received the Mark Twain Prize at the Kennedy Center and gave a moving speech that toed the line of defiance, humor, and poignance. “Twain hated bullies,” he said, “and he deeply, deeply empathized with the weak.” The comic W. Kamau Bell, who performed at the venue shortly after Trump announced his takeover, wrote about the experience, noting that it was his job to “speak truth to power.” And like Bell, my bandmates and I understood why other artists were continuing to cancel their performances. But he, O’Brien, and others demonstrated that there is more than one way to stand up for what you believe.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.