Why Democrats Got the Politics of Immigration So Wrong for So Long

They spent more than a decade tacking left on the issue to win Latino votes. It may have cost them the White House—twice.

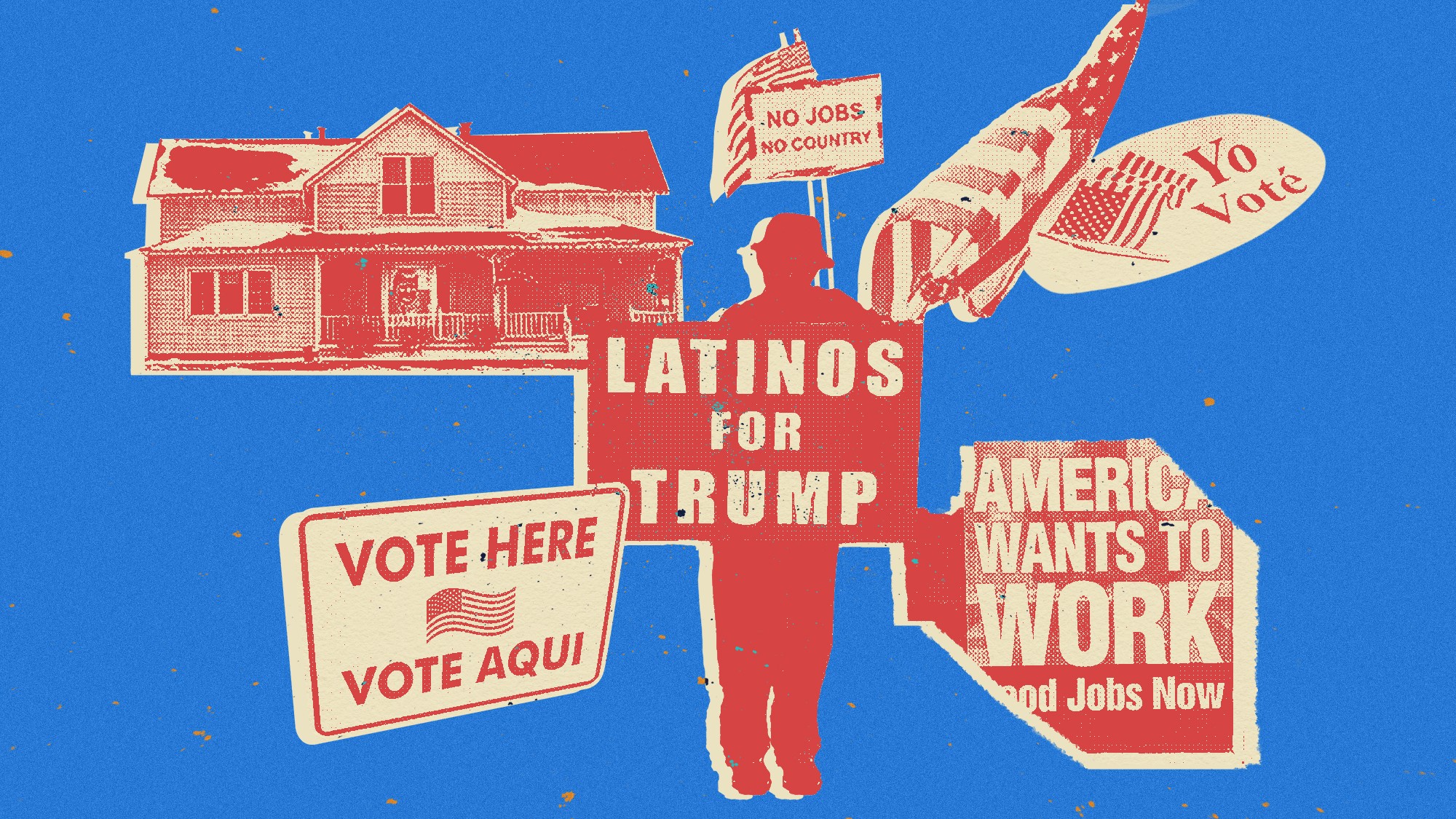

The election of Donald Trump this year shattered a long-standing piece of conventional wisdom in American politics: that Latinos will vote overwhelmingly for whichever party has the more liberal approach to immigration, making them a reliable Democratic constituency. This view was once so pervasive that the Republican Party’s 2012 post-election autopsy concluded that the party needed to move left on immigration to win over more nonwhite voters.

If that analysis were true, then the nomination of the most virulently anti-immigration presidential candidate in modern history for three straight elections should have devastated the GOP’s Latino support. Instead, the opposite happened. Latinos, who make up about a quarter of the electorate, still lean Democratic, but they appear to have shifted toward Republicans by up to 20 points since 2012. According to exit polls, Trump—who has accused South American migrants of “poisoning the blood of our country” and called for the “largest deportation effort in American history”—won a greater share of the Latino vote than any Republican presidential candidate ever. At the precinct level, some of his largest gains compared with 2020 were in heavily Latino counties that had supported Democrats for decades. And polling suggests that Trump’s restrictionist views on immigration may have actually helped him win some Latino voters, who, like the electorate overall, gave the Biden administration low marks for its handling of the issue.

For more than a decade, Democrats have struck an implicit electoral bargain: Even if liberal immigration stances alienated some working-class white voters, those policies were essential to holding together the party’s multiracial coalition. That bargain now appears to have been based on a false understanding of the motivations of Latino voters. How did that misreading become so entrenched in the first place?

Part of the story is the rise of progressive immigration-advocacy nonprofits within the Democratic coalition. These groups convinced party leaders that shifting to the left on immigration would win Latino support. Their influence can be seen in the focus of Hillary Clinton’s campaign on immigration and diversity in 2016, the party’s near-universal embrace of border decriminalization in 2020, and the Biden administration’s hesitance to crack down on the border until late in his presidency.

The Democratic Party’s embrace of these groups was based on a mistake that in hindsight appears simple: conflating the views of the highly educated, progressive Latinos who run and staff these organizations, and who care passionately about immigration-policy reform, with the views of Latino voters, who overwhelmingly do not. Avoiding that mistake might very well have made the difference in 2016 and 2024. It could therefore rank among the costliest blunders the Democratic Party has ever made.

The notion that Latinos are single-issue immigration voters became something like conventional wisdom thanks to the 2012 presidential election. Barack Obama had won more than two-thirds of the Latino vote four years prior, only to see his approval ratings plummet with these voters over the first few years of his presidency. Then, in the summer of 2012, he signed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals executive order promising legal protections for Dreamers—undocumented immigrants who had been brought to the country as children. This, the story goes, galvanized Latino voters just as Obama’s opponent, Mitt Romney, was busy alienating them with calls for “self-deportation.” Obama went on to win more than 70 percent of the Latino vote that fall, and this was widely attributed to DACA. “A crucial piece of Mr. Obama’s winning strategy among Latinos was an initiative he announced in June to grant temporary reprieves from deportation to hundreds of thousands of young immigrants here illegally,” The New York Times reported in a post-election analysis.

But Fernand Amandi, the lead Latino-focused pollster and strategist for both of Obama’s presidential campaigns, told me that Obama won over Latino voters through a relentless focus on the issue they cared about above all others: the economy. Contrary to some media narratives, “the one issue we really didn’t touch was immigration,” Amandi told me. “It never registered as a top issue for Latinos. What they really cared about was pocketbook issues.” For most of his first term, Obama resisted activist demands to embrace more liberal immigration policies because he believed that doing so would cost Democrats crucial votes—a stance that eventually earned him the nickname “deporter-in-chief” from activists. Even so, by the time Obama signed DACA, Amandi said, internal campaign polls showed him polling in the high 60s with Latinos; the executive order might have contributed a few percentage points, at best.

That version of events tracks closely with decades of polling data showing that Latinos—80 percent of whom lack a college degree—view the economy as the most important issue when voting, typically followed by other “pocketbook” concerns such as health care. “In all my years polling this issue, immigration has never been close to the top issue for Latinos,” Mark Hugo Lopez, the director of race and ethnicity research at Pew Research Center, told me. “It rarely even breaks the top five.”

[Paola Ramos: The immigrants who oppose immigration]

Why, then, did so many political experts conclude otherwise? As Mike Madrid, a longtime political strategist who specializes in the Latino electorate, points out in his book, The Latino Century, nonwhite voters are typically assumed to be hyperfocused on ethnic-identity-related policies, such as affirmative action for Black voters and immigration for Latinos. This is so even though the “Latino” category covers an immensely diverse group of people with different cultures, migration histories, and national origins. “The media, politicians, the public—we’ve all been primed to think about the Latino electorate this way for decades,” Madrid told me. So when Obama signed DACA in 2012 and then performed strongly with Latinos, political brains were hardwired to infer causation from correlation. And survey data seemed to back that interpretation up. According to polls released by Latino Decisions, at the time a relatively new firm, DACA had indeed contributed to a spike in Latino support for Obama.

This perception provided an opening for immigration-advocacy organizations. Following the 2012 election, Latino Decisions continued to churn out polls on their behalf showing that—contrary to a large body of public-opinion research—immigration was actually the top issue for Latino voters, and that Latinos had far more liberal views on immigration policy than the rest of the electorate.

Latino Decisions claimed that it understood the electorate in a way that traditional pollsters did not. Matt Barreto, one of the firm’s co-founders, told me that traditional polling outfits had long made a series of methodological errors, such as conducting too few interviews in Spanish and relying on outdated methods to reach voters, that caused them to overrepresent third- and fourth-generation Latino Americans. When these problems were fixed, Barreto argued, a far more accurate portrait came into view.

Critics make the opposite case: The firm, they argue, greatly overrepresents first- and second-generation Latinos, creating the impression of a far more immigration-focused electorate than actually exists. According to Lopez, at Pew, high-quality mainstream pollsters that offer to conduct interviews in either English or Spanish typically find that about 20 percent of Latinos choose Spanish. Latino Decisions, by contrast, regularly conducted closer to 35 percent of its interviews in Spanish, sometimes even more—a signal that it might be oversampling Spanish-speaking households. Several pollsters also complained to me that Latino Decisions isn’t fully transparent about its methodology, including how it defines Latino in the first place.

But Barreto dismisses these and other criticisms, arguing that he is simply better than other pollsters at weighting the various subgroups of the Latino electorate. He pointed out that in 2010, while most polls showed Harry Reid losing his Senate seat, Latino Decisions accurately predicted that a surge of Latino support would deliver him a victory. Barreto, who is also a professor of political science at UCLA, believes that his academic expertise gives him an edge. “Most of these other pollsters haven’t published 83 academic articles on polling methodology and don’t have Ph.D.s,” he told me. “I would invite them to attend the graduate seminar I teach on the subject.”

Within the Democratic Party, Barreto’s side won the debate. In 2015, leaders and allies of the immigration groups that had once sparred with Obama were tapped to help run Hillary Clinton’s campaign. Barreto and his co-founder, Gary Segura, became her pollsters. Their influence showed: From the outset of her campaign, Clinton leaned hard into pro-immigration rhetoric and embraced an immigration agenda well to the left of Obama’s, including a dramatic rollback of enforcement.

That same year, Republican voters nominated Trump. For those operating under the theory that immigration was the wedge issue for Latinos, this was seen as a political gift. Latino Decisions’ pre-election polling found that Latino voters supported Clinton in record-breaking numbers. (“Latino Voters Poised to Cast Most Lopsided Presidential Vote on Record,” it predicted in a blog post.) If that came to pass, Florida would turn from a swing state to solidly blue, and even Texas would be in play. Latino support would drive a landslide victory.

Needless to say, that isn’t what happened. In fact, exit polls suggested that Trump had received a slightly higher share of the Latino vote than Romney had four years earlier. The president-elect’s anti-immigrant rhetoric had not alienated huge swaths of Latinos, and Clinton’s pro-immigration agenda hadn’t won them over. However, the increased salience of immigration did push working-class white voters to support Trump, helping him secure a narrow victory in the Electoral College.

[From the September 2024 issue: 70 miles in Hell]

These counterintuitive findings ought to have prompted some soul-searching within the Democratic Party. Instead, they were almost immediately memory-holed. Exit polls are just as error-prone as any other survey, and many of the most influential groups and pollsters within the party spent the weeks and months following the election disputing the surprising results. “The national exit surveys’ deeply flawed methodology distorts the Latino vote,” wrote Barreto in a Washington Post op-ed. A Latino Decisions poll taken just before the election, which showed Clinton winning Latinos by a historic 79–18 margin, was more accurate, he argued. Other advocacy groups followed suit. “It is an insult to us as Latinos to keep hearing the media ignoring the empirical data that was presented by Latino Decisions,” Janet Murguía, the president of National Council of La Raza (now called UnidosUS), a leading Latino advocacy group, said in a press conference days after the election.

It wasn’t until years later that post-election analyses based on validated voter information would be released, confirming that the exit polls had been basically accurate: Trump had won a similar or slightly higher share of Latinos than Romney had in 2012. (Barreto disputes the accuracy of these studies, arguing that they suffer from the same biases as the rest of the competition’s polling.) But by then, it was too late. The narrative that Latinos had rejected Trump because of his anti-immigration positions had taken hold.

During the first Trump presidency, Democrats shifted sharply to the left on immigration. This was in part a response to the moral atrocity of family separation, but it went beyond just a backlash to Trump. Heading into the 2020 Democratic primary, nearly 250 progressive groups signed a letter urging politicians to endorse positions once considered beyond the pale, including decriminalizing crossing the border. In contrast to the Obama years, party leaders mostly did not push back. At a debate just a few weeks later, eight of the 10 Democratic presidential candidates onstage, including then-Senator Kamala Harris, raised their hands in support of decriminalizing the border.

Although multiple polls found this position deeply unpopular with the public at large, Latino Decisions released its own poll showing that 62 percent of Latino debate-viewers said the decriminalization proposal made them more likely to vote for Democrats. The poll also found that Harris and Julián Castro, the candidates who had taken the most liberal immigration positions to that point, were the top choices for Latino voters. (Neither candidate would come remotely close to winning the nomination.)

[Rogé Karma: The truth about immigration and the American worker]

The eventual winner of that primary was one of the two Democrats who did not support decriminalization: Joe Biden. Still, after the primary, he hired many of the same operatives and pollsters from the Clinton 2016 campaign, and in the general election, he ran on an immigration platform well to the left of Obama’s—one that included promises to reverse Trump’s border policies, place a moratorium on deportations, and expand legal immigration. A September 2020 poll by Latino Decisions found that Biden was leading Trump by 42 points nationally with Latinos, a greater margin than Clinton had achieved.

Biden of course won that election—but not thanks to improved Latino support. In fact, according to post-election studies based on validated voter information, Trump won about 38 percent of Latino voters, about nine points more than he had in 2016 and 14 points more than the Latino Decisions polling had predicted. Yet even this failed to convince Democrats that their theory of the case was wrong. Instead, a new rationalization emerged: Trump in 2020 talked about immigration much less than he had in 2016; therefore, his improved performance among Latinos could be attributed to the lower salience of the immigration issue. The coronavirus pandemic “allowed a window for President Trump to be able to talk about other issues and move away from immigration, which was clearly something that really impacted his prospects for the Latino vote,” explained Gabriel Sanchez, then the director of research at Latino Decisions, in a post-election interview. Besides, Democrats had won the presidency and both houses of Congress. The party had not paid a big electoral price for its slippage with Latino voters. Yet.

The Biden administration entered office with conflicting impulses on immigration. According to a former senior administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they are still in government, the president and some of his closest advisers worried that rolling back Trump-era restrictions too quickly could result in a surge of migrants that would overwhelm an already dysfunctional system. And they believed that strict border enforcement was needed to prevent a political backlash from swing voters. But some more progressive staffers, many of whom had come directly from the immigration-advocacy world, insisted that the White House had both a moral and political obligation to swiftly liberalize border policy. (This description of the administration’s divisions has been confirmed by numerous reports.)

The result was an incoherent immigration policy. In the early months of the Biden presidency, the administration would sometimes keep existing restrictions in place or implement new ones; at other times, it would roll restrictions back, often without any cogent explanation.

Perhaps the purest distillation of this dynamic was the administration’s treatment of Title 42, a provision implemented by Trump in 2020 that allowed the administration to turn away asylum-seekers at the border on public-health grounds. When Biden entered office, he decided to keep Title 42 in place over objections from more than 100 outside groups and plenty of his own staff. A year later, as the progressive pressure continued to mount, the administration announced that it would end the policy. When a federal judge blocked that decision, the administration assured its allies that it would appeal the decision and fight it in court. A few months later, however, in October 2022, the administration reversed course and expanded the use of Title 42. Then, in May 2023, the administration rolled all of that back, allowing Title 42 to expire without any clear plan to replace it. In the following months, border crossings spiked to all-time highs.

Meanwhile, public opinion was taking a right turn against immigration. In 2020, 28 percent of Americans told Gallup that immigration should decrease. Just four years later, that number has risen to 55 percent, the highest level since 2001.

[Rogé Karma: The most dramatic shift in U.S. public opinion]

Latinos were no exception. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Latinos’ views on border security have long been similar to the general population’s. During the Biden administration, Latinos have lurched to the right along with the rest of the country. A Pew poll in March 2024 found that 75 percent of Latinos described the recent increase in border crossings as a “major problem” or a “crisis.” In June, a survey found that Latino voters in battleground states were more likely to trust Trump to handle immigration than Biden. And in focus groups, many Latino immigrants expressed resentment toward what they saw as preferential treatment for recent migrants. Immigration, long believed to be Democrats’ secret weapon with Latino voters, had become an outright liability.

Eventually, the administration realized its mistake. In June, over the loud objections of progressive immigration groups, Biden signed a series of executive actions to stem the flow of migrants. Within months, border crossings reached their lowest levels since Trump was in office. When Kamala Harris took over from Biden as the Democratic nominee, she tacked to the right on immigration, touting her prosecutorial background and promising to “fortify” the southern border.

“The idea that Kamala Harris lost this election because she caved to progressive immigration groups is completely false,” said Barreto, who in 2021 left Latino Decisions with Segura to co-found a new firm, BSP Research, and who served as a pollster for both the Biden and Harris 2024 campaigns. “They were pushing us to run to the left on immigration to win over Latinos. And we ignored them because our internal polling was showing the opposite.”

But Democrats had spent the better part of a decade listening to those groups—and to Barreto’s polling done on their behalf. With just over 100 days to campaign, the vice president couldn’t distance herself from the policies of the administration she had helped run. In one post-election survey, Blueprint, a Democrat-aligned firm, found that the second most important reason that voters (including Latinos) offered for not voting for Harris was “too many immigrants illegally crossed the border under the Biden-Harris administration.” (The top issue, by a single-point margin, was inflation.) Another Blueprint survey found that 77 percent of swing voters who chose Trump believed that Harris would decriminalize border-crossing—perhaps because she had endorsed that position during the 2020 campaign. “Both the Biden and Harris campaigns eventually realized that they had been sold a bag of goods by these immigration groups,” Madrid tells me. “But it was too late. You can’t reverse years of bad policy and messaging in a few months.”

Progressive groups argued for years that increasing the salience of immigration would help Democrats win the Latino vote. In 2024, they got exactly what they’d wished for: Immigration soared toward the top of the list of voter priorities, while Donald Trump centered his campaign around rabidly anti-migrant policies and rhetoric. But instead of winning Latino votes in a landslide, Democrats won their smallest share of them in at least 20 years, if not ever. Some of the statistics are hard to believe. Take Starr County, Texas, which is 98 percent Latino. In 2012, Barack Obama carried the county by 73 points. In 2024, Trump won it by 16 points.

We will never know whether the outcome of last month’s election would have been different if Biden had acted sooner on the border, or if Democrats hadn’t become seen as the weak-on-immigration party over the previous decade. But given how close the final margin was—Trump won Pennsylvania, the tipping-point state, by just 1.7 percentage points—the possibility can’t be ruled out. “There’s a Shakespearean element to all of this,” said Fernand Amandi, the former Obama pollster: Well-intentioned activists, fighting to make immigration policy more humane, “inadvertently helped return to power the most anti-immigration president in modern history.”

[Stephen Hawkins and Daniel Yudkin: The perception gap that explains American politics]

Simply blaming “the groups” would be unfair. Activists are supposed to push the boundaries of the politically possible, even when that means embracing positions deemed unpopular. The job of politicians and parties is to understand what their constituents want, and to say no when those desires don’t match up with activists’ demands. Over the past decade, Democratic leaders appear to have lost the ability to distinguish between the two categories. They seem to have assumed that the best way to represent Latino voters would be to defer to the groups who purported to speak for those voters. The problem is that the highly educated progressives who run and staff those groups, many of whom are themselves Latino, nonetheless have a very different set of beliefs and preferences than the average Latino voter.

Democrats have begun to correct this error, and some liberal immigration advocates have taken the 2024 results as a prompt for an internal reckoning. “It’s imperative that the immigration movement comes together to reflect about the path forward and the kinds of policies that are realistic in the near term for our community,” Vanessa Cárdenas, the executive director of America’s Voice, an immigration-reform nonprofit, told me. “For a very long time, if candidates even bothered to reach out to Latino voters, they would focus on immigration, even though economic issues have always been the top issue,” Clarissa Martínez de Castro, the vice president of the Latino Vote Initiative at UnidosUS, a Latino civil-rights organization, told me. “That was a mistake.”

The 2024 election might have finally disabused Democrats of the notion that they can take the Latino vote for granted. Their job now is to do what democracy requires: earn it.