Wikipedia’s Elon Problem

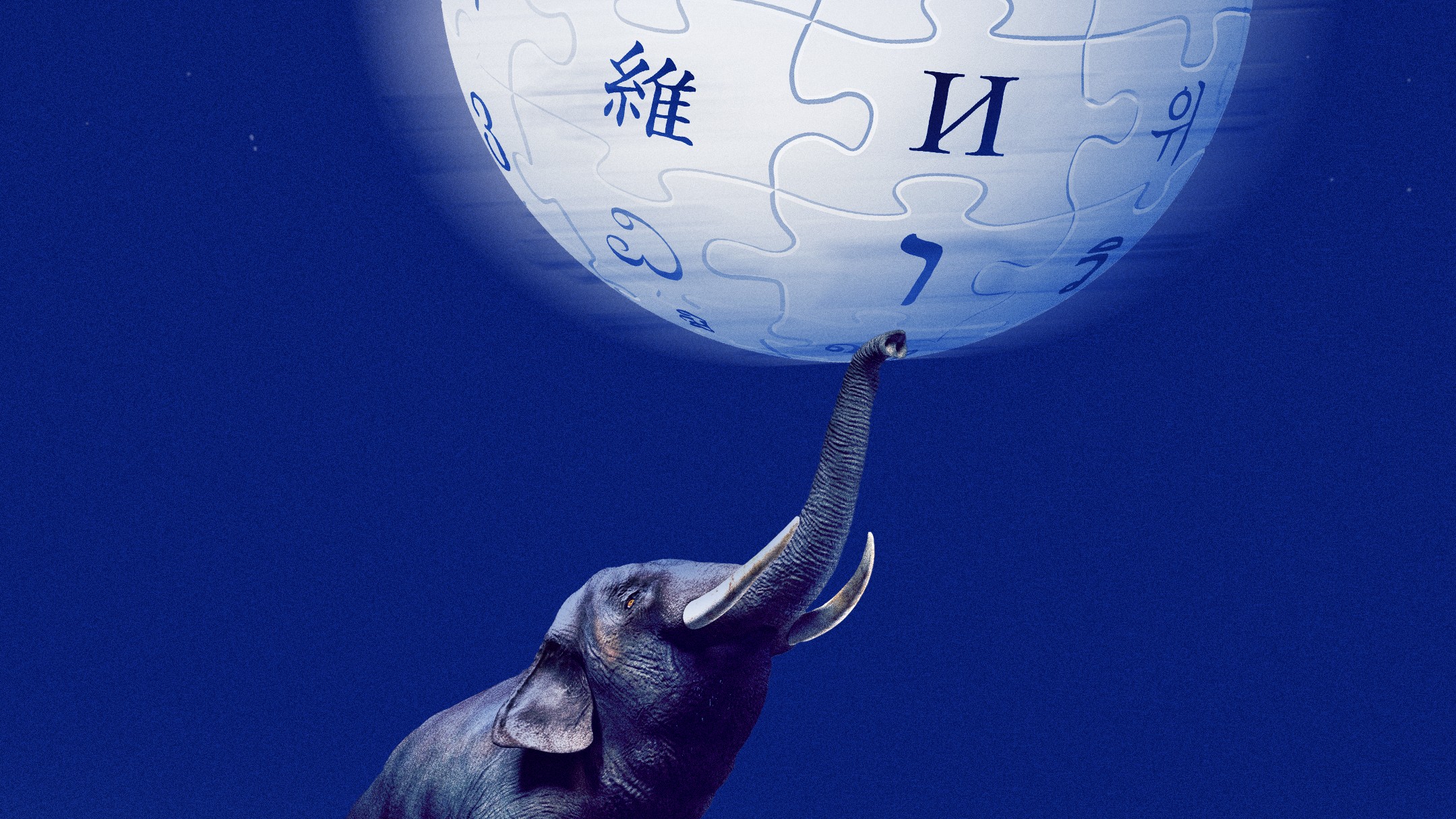

Musk and other right-wing tech figures have been on a campaign to delegitimize the digital encyclopedia. What happens if they succeed?

A recent target in Elon Musk’s long and eminently tweetable list of grievances: the existence of the world’s most famous encyclopedia. Musk’s latest attack—“Defund Wikipedia until balance is restored!” he posted on X last month—coincided with an update to his own Wikipedia page, one that described the Sieg heil–ish arm movement he’d made during an Inauguration Day speech. “Musk twice extended his right arm towards the crowd in an upward angle,” the entry read at one point. “The gesture was compared to a Nazi salute or fascist salute. Musk denied any meaning behind the gesture.” There was little to be upset about; the Wikipedia page didn’t accuse Musk of making a Sieg heil salute. But that didn’t seem to matter to Musk. Wikipedia is “an extension of legacy media propaganda!” he posted.

Musk’s outburst was part of an ongoing crusade against the digital encyclopedia. In recent months, he has repeatedly attempted to delegitimize Wikipedia, suggesting on X that it is “controlled by far-left activists” and calling for his followers to “stop donating to Wokepedia.” Other prominent figures who share his politics have also set their sights on the platform. “Wikipedia has been ideologically captured for years,” Shaun Maguire, a partner at Sequoia Capital, posted after Musk’s gesture last month. “Wikipedia lies,” Chamath Palihapitiya, another tech investor, wrote. Pirate Wires, a publication popular among the tech right, has published at least eight stories blasting Wikipedia since August.

Wikipedia is certainly not immune to bad information, disagreement, or political warfare, but its openness and transparency rules have made it a remarkably reliable platform in a decidedly unreliable age. Evidence that it’s an outright propaganda arm of the left, or of any political party, is thin. In fact, one of the most notable things about the site is how it has steered relatively clear of the profit-driven algorithmic mayhem that has flooded search engines and social-media platforms with bad or politically fraught information. If anything, the site, which is operated by a nonprofit and maintained by volunteers, has become more of a refuge in a fractured online landscape than an ideological prison—a “last bastion of shared reality,” as the writer Alexis Madrigal once called it. And that seems to be precisely why it’s under attack.

The extent to which Wikipedia’s entries could be politically slanted has been a subject of inquiry for a long time. (Accusations of liberal bias have persisted just as long: In 2006, the son of the famed conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly launched “Conservapedia” to combat it.) Sock puppets and deceptive editing practices have been problems on the site, as with the rest of the internet. And demographically speaking, it’s true that Wikipedia entries are written and edited by a skewed sliver of humanity: A 2020 survey by the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that runs Wikipedia, found that roughly 87 percent of the site’s contributors were male; more than half lived in Europe. In recent years, the foundation has put an increased emphasis on identifying and filling in these so-called knowledge gaps. Research has shown that diversity among Wikipedia’s editors makes information on the site less biased, a spokesperson pointed out to me. For the anti-Wikipedia contingent, however, such efforts are evidence that the site has been taken over by the left. As Pirate Wires has put it, Wikipedia has become a “top-down social activism and advocacy machine.”

In 2016, two researchers at Harvard Business School examined more than 70,000 Wikipedia articles related to U.S. politics and found that overall they were “mildly more slanted towards the Democratic ‘view’” than analogous Encyclopedia Britannica articles. Still, the finding was nuanced. Entries on civil rights had more of a Democratic slant; articles on immigration had more of a Republican slant. Any charge of “extreme left-leaning bias,” Shane Greenstein, an economist who co-authored the study, told me, “could not be supported by the data.” Things could have changed since then, Greenstein said, but he’s “very skeptical” that they have.

Attacks will continue regardless. In June, the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank, published a report suggesting that Wikipedia articles about certain organizations and public figures aligned with the right tend to be associated with greater amounts of negative sentiment than similar groups and figures on the left. When asked about bias on the site, the Wikimedia spokesperson told me that “Wikipedia is not influenced by any one person or group” and that the site’s editors “don’t write to convince but to explain and inform.” (They certainly like to write: A debate over the spelling yogurt versus yoghurt was similar in length to The Odyssey. In the end, yogurt won, but three other spellings are listed in the article’s first sentence.)

The fact that Musk, in his most recent tirade against Wikipedia, didn’t point to any specific errors in the entry about his inauguration gesture is telling. As he gripes about injustice, the fundamental issue he and others in his circle have with Wikipedia seems to be more about control. With his acquisitional approach to global technology and platforms, Musk has gained influence over an astonishing portion of online life. He has turned X into his own personal megaphone, which he uses to spout his far-right political views. Through Starlink, his satellite-internet company, Musk quite literally governs some people’s access to the web. Even other tech platforms that Musk doesn’t own have aligned themselves with him. In early January, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta would back away from third-party fact-checking on its platforms, explicitly citing X as an inspiration. (Zuckerberg also announced that the company’s trust and safety teams would move from California to Texas, again borrowing from Musk.)

One thing Musk does not control is Wikipedia. Although the site is far from perfect, it remains a place where, unlike much of the internet, facts still matter. That the people who are constantly writing and rewriting Wikipedia entries are disaggregated volunteers—rather than bendable to one man’s ideological views—seems to be in the public interest. The site’s structure is a nuisance for anyone invested in controlling how information is disseminated. With that in mind, the campaign against Wikipedia may best be understood as the apotheosis of a view fashionable among the anti-“woke” tech milieu: Free speech, which the group claims to passionately defend, counts only so long as they like what you have to say. Attempts to increase the diversity of perspectives represented on the site—that is, attempts to bring about more speech—have been construed as “censorship.” This group is less interested in representing multiple truths, as Wikipedia attempts to do, than it is in a singular truth: its own. (Musk, Maguire, and Palihapitiya did not respond to requests for comment.)

Ironically, Wikipedia resembles the version of the internet that Musk and his peers speak most reverently of. Musk often touts X’s Community Notes feature, which encourages users to correct and contextualize misleading posts. That sounds a lot like the philosophy behind … Wikipedia. Indeed, in a recent interview, X’s vice president of product explained that Community Notes took direct inspiration from Wikipedia.

Strike hard enough and often enough, the Wikipedia-haters seem to believe, and the website might just fracture into digital smithereens. Just as Twitter’s user base splintered into X and Bluesky and Mastodon and Threads, one can imagine a sad swarm of rival Wikipedias, each proclaiming its own ideological supremacy. (Musk and others in his orbit have similarly accused Reddit of being “hard-captured by the far left.”) Musk can’t just buy Wikipedia like he did Twitter. In December 2022, months after he purchased the social platform, a New York Post reporter suggested that he do just that. “Not for sale,” Jimmy Wales, one of the site’s co-founders, responded. The following year, Musk mockingly offered to give the site $1 billion to change its name to “Dickipedia.”

Even if he can’t buy Wikipedia, by blasting his more than 215 million followers with screeds against the site and calls for its defunding, Musk may be able to slowly undermine its credibility. (The Wikimedia Foundation has an annual budget of $189 million. Meanwhile, Musk spent some $288 million backing Trump and other Republican candidates this election cycle.) Anyone who defends free speech and democracy should wish for Wikipedia to survive and remain independent. Against the backdrop of a degraded web, the improbable success of a volunteer-run website attempting to gather all the world’s knowledge is something to celebrate, not destroy. And it’s especially valuable when so many prominent tech figures are joining Musk in using their deep pockets to make their own political agendas clear. At Donald Trump’s inauguration, the CEOs of the companies who run the world’s six most popular websites sat alongside Trump’s family on the dais. There was no such representative for the next-most-popular site: Wikipedia.